The First World War had a devastating impact on the life of those living in the Westhoek region of Belgium. But in a country known as a beer mecca, what impact did the war have on growing one of Belgian beer’s main ingredients?

Words by Melanie Epp

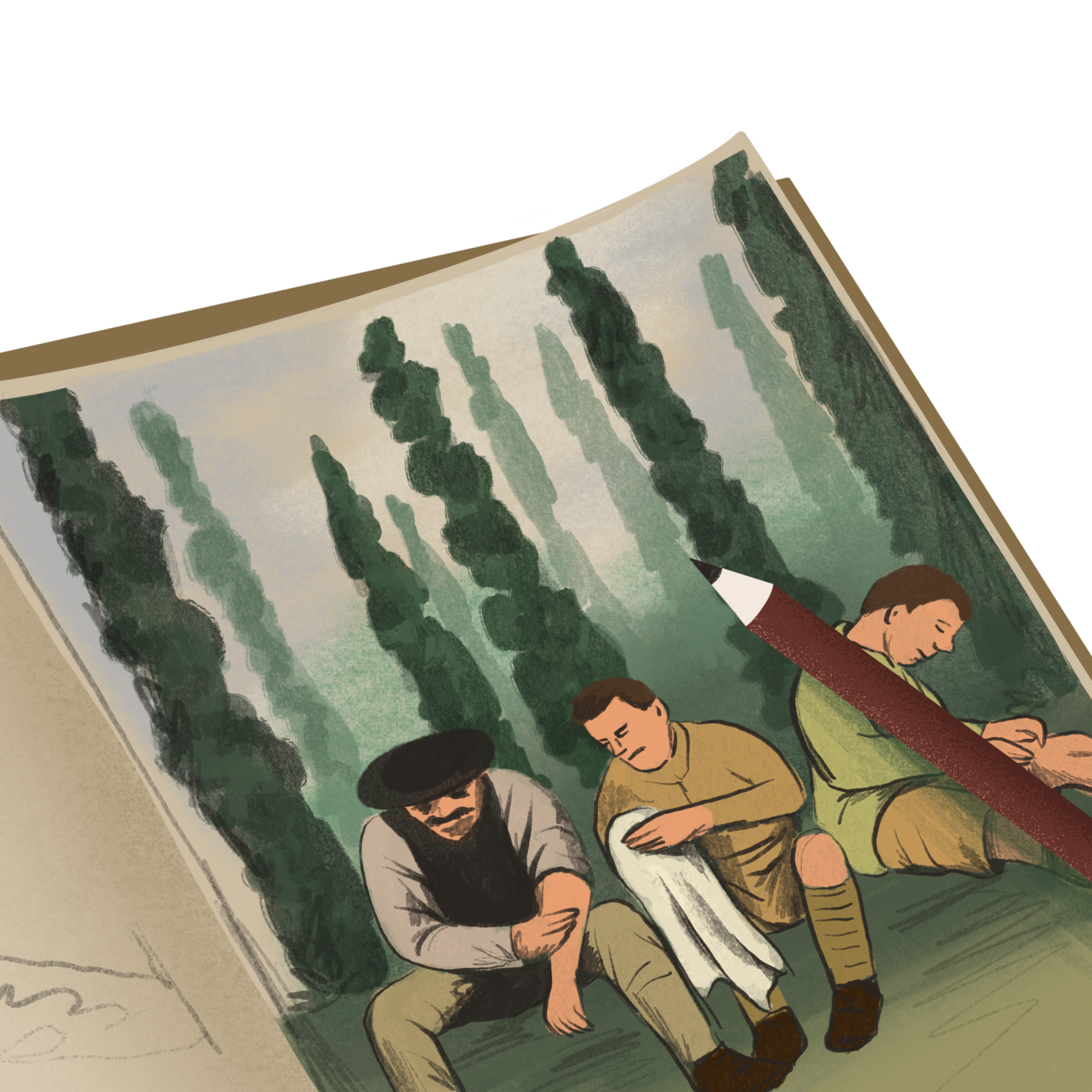

Illustrations by Flore Deman

Edited by Breandán Kearney

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “War Chest” series. Read more.

I.

The Artist Known As “J.M.”

Between 1917 and 1918, an anonymous British soldier, known only by the initials J.M., filled a leather-bound book with 130 sketches from the frontlines of World War I. Most of the watercolour and ink images, which now sit in an archive in Victoria, Canada, depict the bleak reality of war. The yellowed pages of J.M.’s sketchbook are filled with images of military camps and battlefields; trenches and dressing stations; casualties and graves. There are several disturbing sketches depicting horses dying of gas poisoning. Each of these images offers a vivid insight into the realities of the Great War.

One particular sketch stands out. Three British soldiers sit side by side on a mound of earth on a hop farm somewhere in Flanders. One man appears to be cleaning his hands with a towel, while another is rolling up his sleeves. The third man appears to be resting quietly in the afternoon sun.

The image, entitled “Hop-picking in Flanders”, paints a picture of comradery through hard work, but also of tranquility. It gives the viewer a much-needed reprieve from the ghastliness of the artist’s other sketches. The setting must have provided the same for the soldiers—clemency amid the horrors of war.

What I found most intriguing about the sketch were the hops. As an agricultural journalist, I’d written stories about food production during the Great War. What I hadn’t explored was hops and beer and the war’s impact on their production.

Coming from Canada, where prohibition was in full swing during the war, I just assumed that the production of beer and the growing of hops had stopped so that farmers could put greater emphasis on feeding the masses.

J.M.’s sketches told me I was wrong.

II.

Party Town

Poperinge is the “Hop Capital” of Belgium. Visitors who enter the city are greeted by a statue of a giant hop bell. Surrounded by stakes, the bell is situated in the middle of a roundabout. The city and its surroundings are the ideal place to grow hops: its mild climate and fertile soil provide the perfect environment for abundant and vigorous growth.

The hop plant Humulus lupulus produces flowers or hop bells that are used to add flavour, bitterness, and foam stability to beer. Hops are also valued for their antibacterial properties which help to guard against infections from undesirable microorganisms. Depending on the variety used, hops contribute flavours and aromas that can be floral, citrussy, piney, or spicy in nature. It would be difficult to overstate the role of hops in the production of beer.

The hop’s status has been raised to that of a virtual patron saint in Poperinge. Hop farms are as ubiquitous to the region as those who revere them, but production now is nothing like it used to be. The 1846 census shows nearly 3,000 hectares of hops production in the entire country. Today, only 181 hectares remain, 155 of which are grown around Poperinge. What happened?

During the Great War, Poperinge became the gateway to the battlefields of the northern Ieper (Ypres) Salient. Here, much of the focus shifted from agricultural production to protecting the homeland.

It is estimated that one million soldiers from more than 50 countries were wounded, missing, or killed in action between 1914 and 1918 in Flanders alone. Entire villages and cities were decimated. Conditions were particularly brutal in Ieper where war raged continuously for four long years.

Behind the frontline, Poperinge served as an important rail centre, a distribution hub for supplies. The railway transported fresh troops to the trenches, carted casualties to clearing stations, and hauled weary soldiers back for rest.

Famous for its booze and brothels, Poperinge became a party town that offered Allied soldiers liberation, albeit briefly, from the terrors of the trenches. And while Poperinge did provide reprieve from the death and destruction of the frontlines, drunken debauchery wasn’t exactly the best form of respite. The thousands of soldiers who passed through the town were five times more likely to suffer from venereal disease than trench foot. One of the soldiers passing through might have been J.M., searching perhaps for comfort, quietude, and a place to sketch.

III.

An Agricultural Journalist

In some ways, I have always felt tied to Belgium, and in particular, Flanders. I first visited the country in 2014 to attend a dairy conference at the University of Ghent, a city that would later become my home. My flight touched down in Brussels on 4 August, exactly 100 years after the Germans invaded Belgium. As the train crawled from Brussels to Ghent, the view out the window reminded me of the poem In Flanders Fields by Canadian army doctor John McCrae. In the poem, McCrae describes an otherwise barren military graveyard being blanketed in red poppies, a vulnerable but irrepressible flower which blossoms blood red and suggests both ode and elegy. Until that day poppies had been a part of my cultural memory, but the only ones I’d seen were pinned to the lapels of winter coats each November. Now they were everywhere.

I share my hometown of Guelph with John McCrae. In my teens, I lived just around the corner from McCrae House. My siblings went to John McCrae Public School. Over 130 street signs in Guelph are named in honour of the city’s war dead. Each sign carries a bright red poppy, setting it apart from the signs of other streets. The poppy is as ubiquitous in Guelph as the hop bell is in Poperinge.

In October 1914, some 30,000 Canadian troops made the long haul to Britain and then to Belgium. John McCrae wouldn’t arrive until early 1915. I know this because I visited McCrae House one last time before I moved to Belgium in October of 2014. I was to begin a new life with my West Flemish boyfriend, himself born in Poperinge. It was the start of a very different education than the one I’d received in my Canadian classrooms.

Canadian high school and university textbooks emphasise Canada’s role in the Great War. They highlight the many battles: Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge, and the Battle of the Somme. They raise our soldiers to the status of heroes, while carefully depicting the horrors of trench warfare—hungry, opportunistic rats, the pervasiveness of sticky mud and crawling lice, and the smell of death and rot and mustard gas.

In English class we studied the great war poems—by McCrae, but also by Robert Graves, Rupert Brooke, Sigfried Sassoon, and Wilfred Owen. In history class we learned that it was illegal to consume alcohol in Canada during the war. Prohibition was seen as a social sacrifice and patriotic duty. Abstinence, it was believed, would help win the war.

Looked at through an historical lens, I suppose that makes sense. But for war weary soldiers on the front lines, alcohol seems to have been often consumed to still the mind and renew the spirit. If soldiers had access to beer, where and how was it being made? Grain and hops are vital to the production of beer. Were farmers forced to stop during the war or did they somehow labour on regardless? Was there any place near Poperinge with even a hint of normalcy in life?

IV.

Frontline Farming

It was a warm, sunny day when I met Chris Vandewalle in Ieper. Over a Poperings Hommelbier, Chris—a local brewer and professional archivist—provided historical background on agricultural production during the Great War. Tracing his finger along a map, he pointed to the front line, which stretched from Nieuwpoort through Diksmuide to Ieper. One side of the frontline had been occupied by the Germans, while the other side had been “free”, he said.

Situated in “free Belgium”, Poperinge was overseen by two governments: the military government and the local government. When the war started in October 1914, the region was immediately evacuated. Many of the region’s farmers chose to stay behind. But they weren’t allowed to return to work until the spring of 1915 when the military government gave them the okay.

Agricultural production in the region was overseen by the military government, explained Chris. Rules around production, prices, and the distribution of goods changed many times throughout the war, but farmers, for the most part, were still allowed to farm. “Soldiers and military people were very surprised by how closely farmers were working to the frontline,” Chris said. Evidence of this can be seen in aerial photos from the time, where working farms and their crops are clearly visible alongside the battlefields and trenches.

Before the war, farmers were free to grow what they wanted and in whatever quantity. They grew hop varieties that are virtually impossible to find today: Groene Bel, Coigneau, and Witte Rank. But as the region became heavily populated by soldiers, civilians, and refugees, the need for food became greater than hops.

In the autumn of 1915, farmers were given permission to harvest, and soldiers were recruited to assist. Many of the soldiers lived on nearby farms, and some even worked the newly established military farms. These farms were run by local boys, sons of farmers, who brought with them knowledge of crop production, including hops. It might not have been unusual then to see soldiers picking hops as is pictured in J.M.’s sketch.

By 1917, price fixing, monitoring, and appropriation of crops all became the norm. Two major evacuations—one in April 1916, and one in July 1917—left farmland unprotected. When the farmers were able to return, much of their property was destroyed, and most of the harvest and livestock stolen.

Hops production changed vastly at this time too. Surviving records show the weight of hops harvested during the war years. Sources from the city archives and Hopmuseum Poperinge reveal there were approximately 990 hectares of hops grown in the Greater Poperinge region in 1895. By 1917, that number had dropped to 463 hectares. Historical records attribute this loss to an inability to acquire the stakes and wire needed to hold up the creeping vines, much of which had been stolen during the evacuations. And with all efforts focused on the war, helping hands come harvest were also in short supply. It was perhaps one of the darkest times for Poperinge’s most proud agricultural endeavour.

V.

The Tops

Scanning the records of the weight of hops harvested during the war years, two statistics, however, catch my attention. I see that not all municipalities in Poperinge had experienced a decline in hops production.

In fact, two municipalities of Poperinge saw a small bump: Proven and Roesbrugge-Haringe.

Hop farmers Wout Desmyter and Benedikte Coutigny of Proven’s ‘t Hoppecruyt farm suggest I meet with a local historian.

82-year-old Ivan Top has turned his living room into a study that’s filled with shelves of notebooks and binders stuffed with newspaper clippings, letters, maps, and photographs. He’s written biographies about nearly every family in the village. He likes to create literary sketches of select individuals some 50 years after they’ve perished.

Hops and history run in Ivan’s blood. In 1905, Ivan’s grandfather, Marcel Top, worked alongside Hector Desmytter, Wout’s great grandfather, to establish the United Hop Farmers of Proven, a guild that worked to protect and strengthen the quality and production of hops in the region. Later renamed Sint Rochus, likely after the patron saint of beer brewers and farmers in Belgium with the same name, the guild conducted field trials, testing fertilizer applications, picking and drying techniques, pest control, and varietal selection.

The United Hop Farmers of Proven also established a professional magazine, De Hopboer (The Hop Farmer), that offered timely tips for improving production. The guild started a regional competition for hops production, which led to the introduction of the Witte Rank variety to bigtime brewers in Ghent and Liege. While the variety didn’t survive the war, the guild’s work laid the foundation for the success of the region’s remaining growers after the war.

Ivan’s uncle, Roger Top, was also instrumental to the success of hops production in the region. A hop grower himself, Roger was the first in Belgium to adopt the automatic hop picking machine, and first to test a semi-automatic dryer. In his later years, he helped with the reorganisation of the Hopsmuseum in Poperinge, and advocated strongly for the use of Flemish hops in Belgian breweries.

As I sat down next to him, Ivan shoved stacks of documents aside on his desk, and reached for a pile of clippings on hops production in the region during the Great War. Soldiers and Chinese immigrants had constructed a railway that led from the front lines through the city of Poperinge and all the way to its last stop in Proven.

While the peaceful village is home to just 1,400 inhabitants today, at that time, it was alive with thousands of British troops. Locals opened their homes to provide sleeping quarters for soldiers and stables for their horses. Evidence of this is still visible today, as military officials recorded the number of men and horses in each home on the outside walls of the houses.

While other parts of unoccupied Belgium, particularly Poperinge, were riddled with reminders of war, Proven stood out as a virtual paradise. Perhaps it’s because business was bustling. Unlike the Germans, who simply seized what they needed, British troops paid for their supplies. Local women offered laundry services and opened their homes as makeshift cafés, serving beer produced in the north of France. It did a tidy business as a hop and beer village, tripling production during the years of the Great War, according to Ivan.

During the war, Proven was not only a thriving hop growing community, but it was a vibrant village, alive with economic activity and social interaction. Against the backdrop of such death and destruction, it provided soldiers and locals with a sense of peace.

VI.

The Outbuilding

After visiting Ivan, I made my way up the road to ‘t Hoppecruyt, home to Belgium’s longest continually hop farming family. The old farmhouse sits in the middle of the village across from Sint-Victorkerk. The house looks today much as it did back then. Wooden beams run through the ceiling, and the floor is covered in ancient, decorative tiles. The ceilings are so low, and Wout so tall, that he had to duck as he passed through the doorway to greet me. As he and his son, Roel, headed out the door, Benedikte took me on a tour of the farm.

‘t Hoppecruyt is one of just 23 remaining hop growers in Belgium. Of those, 18 hail from the region around Poperinge where 155 hectares are cultivated each year. The farm itself is older than the five generations of Desmyters who lived there, all of them hop farmers. Built in 1777, it has been surrounded by hops for as long as records exist.

The house itself is surrounded by outbuildings, and behind them grow the hops. Benedikte points to a place where one outbuilding had, until recently, stood. The British Royal Air Force had turned the nearly 250-year-old ‘t Hoppecruyt farm and surrounding village of Proven into an encampment during the war, she explained, and the outbuilding had served as a barracks of sorts. Soldiers who passed through carved their names on the wall.

Like a snapshot in time, the outbuilding remained as it was for nearly one hundred years. But as the years wore on, so too did its façade. Wout and Benedikte made the decision to carefully dismantle the old building, setting aside the pieces to donate to a war historian in Passchendaele. The historian hopes to one day resurrect the building, said Benedikte.

During the war, the farm continued to produce hops, but also other staples. Soldiers were able to buy meat and vegetables on the farm. Their location, far from the frontlines of the war, and the fact that the British provided good business, seems to have protected them from the fate of the region’s other hop producers. Benedikte believes it’s one of the reasons they can still produce hops today. “I think we were a little bit lucky here,” she said, looking around. “It was the good life here during the war.”

The evidence of what happened here is everywhere. On a nearby potato farm, abandoned trench railway ties get a new life as fenceposts. They’re linked together with rusted and tangled barbwire. In a neighbouring café, the base of an old bomb serves as a makeshift ashtray, and the shells of larger bombs are used as flowerpots, nurturing life where they once brought death.

As Benedikte and I said our goodbyes, I turned to the space where the barracks once stood. The pieces of outbuilding were no longer there, so I couldn’t check whether J.M., the mysterious sketchbook artist, had carved his initials into the wall.

We know J.M. survived the war because one of his sketches is dated from 1920. We know his sketches were drawn on special stationary bearing the coat of arms of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. We know from the drawings themselves that he was likely stationed in France and Belgium in 1917 and 1918: the locations he mentions are around Ieper and Menin, not far from Poperinge and Proven. We know he had a daughter called Adele, to whom he dedicated his sketches. And we know his works ended up in a special archive in Victoria, Canada, where history professors today are still trying to uncover his true identity.

While most of the depictions in J.M.’s sketches are bleak, every so often he offers a moment of reprieve, a little piece of paradise amidst the horrors of war. Hop stakes are a common feature of the sketches which offer such reprieve and celebrate such tranquility. Sometimes, these hop stakes are the focal point of the picture, as in “Hop-picking in Flanders”. In other sketches, such as those entitled “Abeele November” and “Picturesque Flanders”, the large structures which support the growing of the hop bines sit unassumingly in the background. They emerge stealthily from behind a mist or appear as a virtual silhouette in front of a setting sun, reminding us that they are part of this place, and that they have survived more than we might ever know.

*