Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock moved from Belgium to Chicago in 2014. Six years later—after a terrible cycling accident on Lake Michigan and in the middle of a global pandemic—they launched a new brewing project back in Belgium, inspired by their experiences in the US.

Words by Breandán Kearney

Photography by Cliff Lucas

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth-Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “New Arrivals” series. Read more.

I.

April Fools’

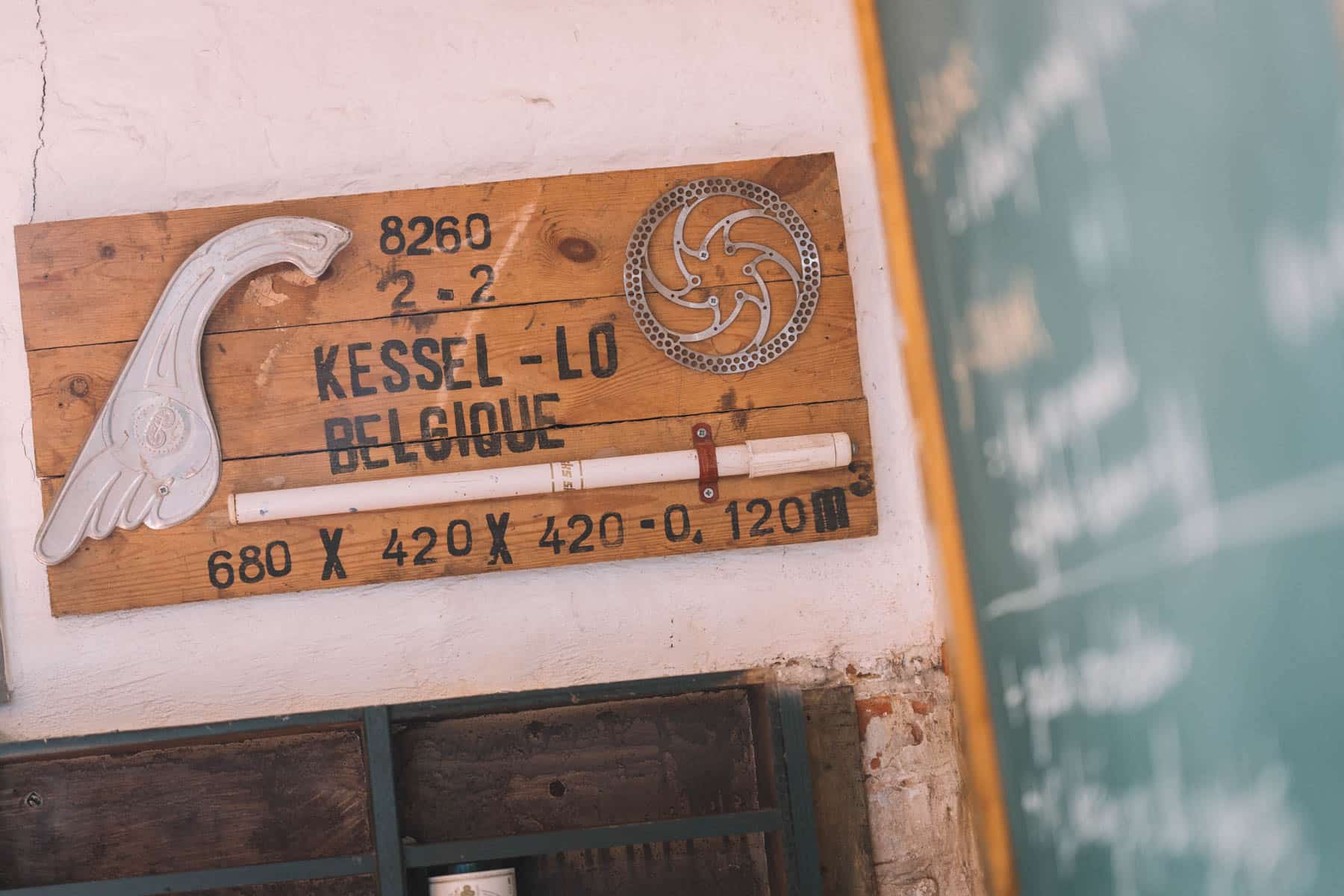

Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock brewed their first commercial beer as Brouwerij De Coureur on 1 April 2020. That brew was to mark the beginning of a life-changing business project, a small brewery and taproom in the Kessel-Lo neighbourhood of Leuven in Belgium’s Flemish Brabant province.

The couple, in their early forties, had moved back from abroad to their homeland of Belgium, excited to start a new life and career. They had searched hard to find a unique space in the city. They had put down a significant capital investment from their own private funds on tanks and equipment, their personal savings from years of work. They had developed beers over the previous decade, in homebrew experiments and in commercial collaboration with other breweries. And they had spent months working towards excise approvals and business administration.

Now that their first brew was complete, they were ready to open.

They named their brewery for the coureur—rider in cycling speak—and all of their beers would be named following this cycling theme. They intended to serve three core beers alongside a new rotating beer each month: The Colleke (referring to a “little hill” that’s easy to conquer on the bike) would be a Cream Ale of 4.5% ABV; the Kuitenbijter (literally “calf biter”, a more nasty hill which burns your calves) would be an IPA of 6.3% ABV; and the Souplesse (riding “op souplesse” means to ride effortlessly) would be a Golden Tripel of 6.9% ABV.

As cycling enthusiasts—both sporting and recreational—they wanted to combine two of Belgium’s most iconic past-times: beer and bikes. They refused to buy a car. They hoped people would visit their brewery on bikes, whether it was families on longtails, bakfietsen, or cargo bikes, recreational cyclists taking a break from their escapades in the hills around Leuven, or those pulled to the city for international cycling tournaments. They intended to showcase cycling culture across their taproom.

At a deeper level, their vision for the brewery was to be a true neighbourhood brewery and taproom, serving beer only on draught, with ambitions not to grow and distribute, but to embed themselves more deeply into the changing community of Kessel-Lo. As part of this, they wanted to interact with their community in a physical space that facilitated conversation and mutual respect, as well as communicate with consumers online in ways other Belgian brewers had not been keen to do.

However, in the month leading up to their first brew, the world fell apart. In early March 2020, a coronavirus began spreading throughout Belgium, the beginning of a pandemic which would result in more than 4.5 million confirmed cases and more than 32,000 deaths in the country.

Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock watched the news each week after meetings of Belgium’s National Security Council; on the 12th of March, schools, discos, cafés, and restaurants were closed, and all public gatherings were cancelled; on the 17th of March, strict social distancing measures were introduced and severe penalties set out for non-compliance; and then on the 20th of March, Belgium closed its borders to all non-essential travel.

On the 1st of April 2020—April Fools’ Day—they brewed their first beer without knowing when they might be able to pour it for people in their taproom. They had no idea when they’d be allowed to hug their families again, never mind when they would be able to serve their beer to customers.

Brouwerij de Coureur was born in the midst of one of the deadliest pandemics in the history of the world, forced to fight for its survival before it had even started. But it wasn’t the only challenge its owners faced before their project got off the ground.

Brouwerij de Coureur, you see, began with a terrible accident.

II.

New World

When he was three years old, Bart Delvaux’s parents moved from Leuven to Holsbeek, 8 kilometres to the north east of the city. When his parents went to work, they would drop him off at his grandmother’s place in Kessel-Lo, a suburb in the east of the city of Leuven. “I kind of grew up in Kessel-Lo,” says Delvaux. Ine Van der Stock grew up in Rotselaar, just to the north of Leuven and right next to Holsbeek. The couple met at University in Brussels, but in 2000, they bought a house together in the place that felt like home more than anywhere else: Kessel-Lo.

Ine Van der Stock had experience in both project management and sustainable tourism initiatives, working as a Tourism Manager at the Hoge Kempen National Park and then as a Project Manager in Tourism Education with the ViaVia Tourism Academy. Delvaux worked as a project manager with Serrala, a German software development company specialising in global financial automation. Delvaux had experience in advising corporate treasury departments in processes and software across the financial supply chain. The dream was to work hard as a consultant, and then at the age of 40, with a financial safety blanket, change career and do something completely different.

Delvaux became interested in beer while drinking in various cafés with seven of his friends. Together the eight friends started a company in 2011 called Nattelore, contracting beer at various facilities, including Anders and Hof ten Dormaal. The experience pulled Delvaux into the beer world, exposing him to new beer festivals, the commercial world of distribution, and the complexities of production.

Van der Stock didn’t drink beer. In fact, she suffered from an allergy to alcohol. But she saw how fascinated Delvaux was becoming with the beer world, and supported him with the project. As time went on, she also grew to enjoy spending time around the community of people in the beer industry in Belgium.

But just as beer in Belgium was experiencing a shift in 2013, with new breweries opening and the influence of foreign styles beginning to make a mark, Delvaux was offered an opportunity by Serrala. They were relocating their office in the United States from Ann Arbor to Chicago and wanted him to move out there and manage the project. Van der Stock was excited and was keen that they go for it. The USA would offer a chance to see new places and meet new people. In 2014, the couple got on a plane and moved their lives to Chicago, Illinois.

They immediately loved the city and threw themselves into new opportunities, both in work and travel. Delvaux worked hard for Serrala and Van der Stock began giving tours as an independent city guide for Dutch speaking visitors to Chicago. She even wrote a Chicago e-guidebook in Dutch. The couple loved adventures, and in the summer of 2015, they booked a big hiking trip to Alaska.

Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock, however, would never make it to Alaska.

III.

The Accident

Two weeks before the Alaska trip, on Saturday 18 July 2015, Bart Delvaux went for a Saturday afternoon cycle on the shore of Lake Michigan, near Oak Street Beach, while Van der Stock was at the theatre. A group of people heading back from the beach towards the city centre walked across the bicycle lane, ignoring cyclists and leaving beach towels trailing on the path. Delvaux swerved to avoid them, but he hit a stone, causing him to crash his bike and fall to the ground. His bike was severely damaged, his cycling jersey badly ripped, and his body covered in blood. Although he didn’t know it at the time, he had broken his hip.

He lay there for a while, unable to move. The pedestrians who had walked across the bike path asked him if he was okay, but when he told them he couldn’t move his leg, they left quickly. “They were running away from me,” says Delvaux. “They didn’t want to have a claim.”

Instead of calling an ambulance, Delvaux picked himself up, and with a broken bike and a broken hip, cycled the 12 kilometres or so from Oak Street Beach back to their Chicago apartment in the Andersonville area of west Edgewater. He had a shower and called Van der Stock to tell her he wouldn’t be able to go to the friend’s barbecue they had scheduled for that evening. “I went to bed to get some sleep,” says Delvaux. “Still thinking it’s going to be just bruising.”

“I didn’t sleep very well,” says Delvaux of that night. “I couldn’t move my leg anymore.” It was only when the pain became unbearable the next morning that Delvaux agreed to go to the closest hospital. “They were rather angry at him,” says Van der Stock.

When they got to the hospital the doctors quickly confirmed through X-ray that he had broken his hip and a few hours later, he was lying in an operating theatre undergoing emergency surgery. The surgeon told him that he had been lucky. He had narrowly missed out on an arterial injury which might have led to a haemorrhage. “An artery could have snapped,” explained Delvaux. “He could have lost his leg,” says Van der Stock.

Delvaux underwent surgery and was confined to crutches. Alaska had to be cancelled, of course, and the incident left the couple deflated. After a few days, they decided that they wouldn’t sit around, and that they would go somewhere else instead, partly to take their minds off the accident and partly because Delvaux had already taken two weeks off work.

They went on a day trip to Sawyer, Michigan, a quaint midwestern town hugging Lake Michigan, just over an hour outside of Chicago to the east. Van der Stock drove. Delvaux hobbled. Feeling peckish, Delvaux and Van der Stock popped into Sawyer’s local brewpub, Greenbush Brewing. It felt like a hidden gem.

“It was just before lunch and it was packed,” recalls Delvaux. “We had the last table. People were having a beer. People that knew each other, people that had no idea who the other one next to him was. At the bar, there was a guy in a suit, maybe a lawyer or some other executive, next to a guy that was probably the guy that would pick up the trash. They had a beer together and talked to each other and were having a burger or some hummus and pita bread with that. It was an amazing atmosphere.”

Up until that point, Delvaux had been drinking Belgian beer in Chicago which, “we knew was going to be good,” he says. “For us, until then, the American beers were the Budweisers and Coors.” The Greenbush experience changed that. “The beer was great, which I did not expect,” recalls Delvaux naively of Greenbush, surprised by its full flavour and diversity of styles.

The discovery sparked a series of trips all over Chicago and the midwest to visit brewpubs and brewery taprooms. “In total, I visited breweries in 49 states,” says Delvaux. “It was amazing to find small places that made great beer, and most of the time, really innovative, different styles of beers.” One thing they noticed was that many of these taprooms did not package beer in bottles or cans, but only served beer on draught. Those that did offer takeaway beer were using growlers—glass, ceramic, or stainless steel jugs used to transport draught beer and filled by taprooms for customers using a specific growler filling station.

Delvaux and Van der Stock loved the growler system. They loved Chicago. They were loving their lives. The cancelled Alaska trip had left them feeling down, and a little lost, but the subsequent trip to Sawyer had opened up a whole new world to them; one that built on their previous interest in beer from their days dabbling in the Nattelore project back in Belgium and that educated them on a whole new world of beer styles and community taprooms here in the US. “We were like, well, we’re going to stay here as long as we want,” says Ine Van der Stock.

But that was before the results of the 2016 presidential election.

IV.

Ballot

On 8 November 2016, Donald John Trump, an American media personality and businessman, was elected as the 45th president of the United States. “I still remember the election day,” says Van der Stock. “It felt like being in a nightmare, and especially in Chicago, because Chicago is Obama town.” Trump fuelled controversy with his views on race and immigration, incidents of violence against protestors at his rallies, and numerous sexual misconduct allegations. The tone of the election was polarising and divisive.

“Chicago all of sudden had that really negative energy and lots of demonstrations started to go on,” says Van der Stock. “You remember that Donald Trump every day said something stupid and it just was awful. It’s sort of then that, in our mind, things started to change. After a couple of months, I remember I had to stop hearing the news because you just got depressed.” For the first time, Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock started talking about the possibility of leaving the United States.

At breakfast one Sunday morning in their Chicago apartment, Van der Stock noticed how absent Delvaux seemed. “I was just getting too comfortable,” says Delvaux. “There was no challenge.” He was working 80 hour weeks. It was a couple of months before Delvaux’s fortieth birthday and Van der Stock asked him a question.

She asked him what he really wanted to do. Did he want to continue consulting or did he want to follow an old dream of beginning a new career? Reflecting on the Nattelore project and on their experiences in US brewpubs, Delvaux answered that he might like to run a small brewery and taproom.

Van der Stock asked more questions: about where the brewery might be located and what type of beers it might produce. “Everything came out of him from his heart instead of his head,” she says of Delvaux’s answers. “I thought, well, this is viable in our situation. We can do this.”

V.

Home

At the top of the list of potential locations for Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock’s brewery project was the place they had always considered home back in Belgium.

Kessel-Lo has a population of 26,000 and, uniquely for a city borough, its own postal code (3010). “Kessel” is from the Latin “Castellum” for fortress and “Lo” for forest clearing.

At one time an unremarkable city suburb, Kessel-Lo has transformed in recent years to be a lively and highly desirable place to live for professionals, creatives, and young families. Its disused spaces have become recreational parks and its old industrial buildings are now food halls and sports centres. It’s also the scene of densely-packed, but characterful terraced housing, where close proximity has nurtured strong neighbourhood connections.

People in Kessel-Lo cycle to their destinations, across the borough, but also into the city centre of Leuven and back. It made it all the more significant to brand their brewery in this neighbourhood with a cycling theme.

Delvaux and Van der Stock were also keen not to ignore the impact of the accident on Lake Michigan in the formation of their brewery. “We wanted to turn the negative experience into something positive,” says Delvaux.

They had a plan. They had a brand. Now, they just needed a building.

VI.

A Hidden Gem

Delvaux and Van der Stock knew the space in which they installed their brewery would be crucial to its identity. “Our idea was to have a brewery in what they call—in the States—‘a hole in the wall’,” says Van der Stock. “A hidden gem. . . we wanted it to be a place to discover.”

Van der Stock travelled back to Kessel-Lo to put the feelers out. She told her family, friends, and business acquaintances in the neighbourhood about their brewery project and the type of space they would need: an old building with a specific character. A couple of weeks later, she received a phone call from someone with a workshop building they no longer needed.

When Van der Stock first saw it, she knew it was perfect. “You’re dancing inside,” she says. “But you have to stay serious because you still want it.” The building dated back to 1927, used as a Renault car workshop until the 1970s. A car port opened on a residential street of terraced houses, with a spacious atrium leading into a long, high-ceilinged warehouse space. Delvaux travelled a few weeks later from Chicago to look at the space and loved it. After a short price discussion, they managed to secure the property without it ever having been put up for sale publicly.

Over the next two years, Delvaux and Van der Stock visited breweries in the region and local associations to introduce themselves and inform them of their plans. At first, some neighbours on the Borstelsstraat were concerned. “They were like, Oh no, not another AB Inbev,” says Van der Stock. (Anheuser-Busch InBev, with its headquarters in Leuven, is the largest brewing company in the world). “But when they heard the plans, they were very positive.”

Everything took longer and cost more than they had first anticipated. “It’s just so tough in Belgium to start up a business,” says Van der Stock.

“Federal department ‘A’ says you cannot do that,” says Delvaux. “The local department ‘B’ says you have to do that. And then it’s like, okay, so how do we find the middle of those to make it fit? Oh yeah. That is going to cost you €50,000. Oh, shit.”

The couple visited other breweries in Belgium, to see if they could learn about ways to circumvent the delays and confusion. “Everyone told us, don’t do it,” says Van der Stock. “They told us not to start a brewery.”

They completed the renovation of the building themselves, ensuring it would be fit for purpose for their brewing equipment and taproom bar. “During the renovation of the building, I lost 15 kilos,” says Delvaux. “I lost three years of my life,” Van der Stock quickly adds.

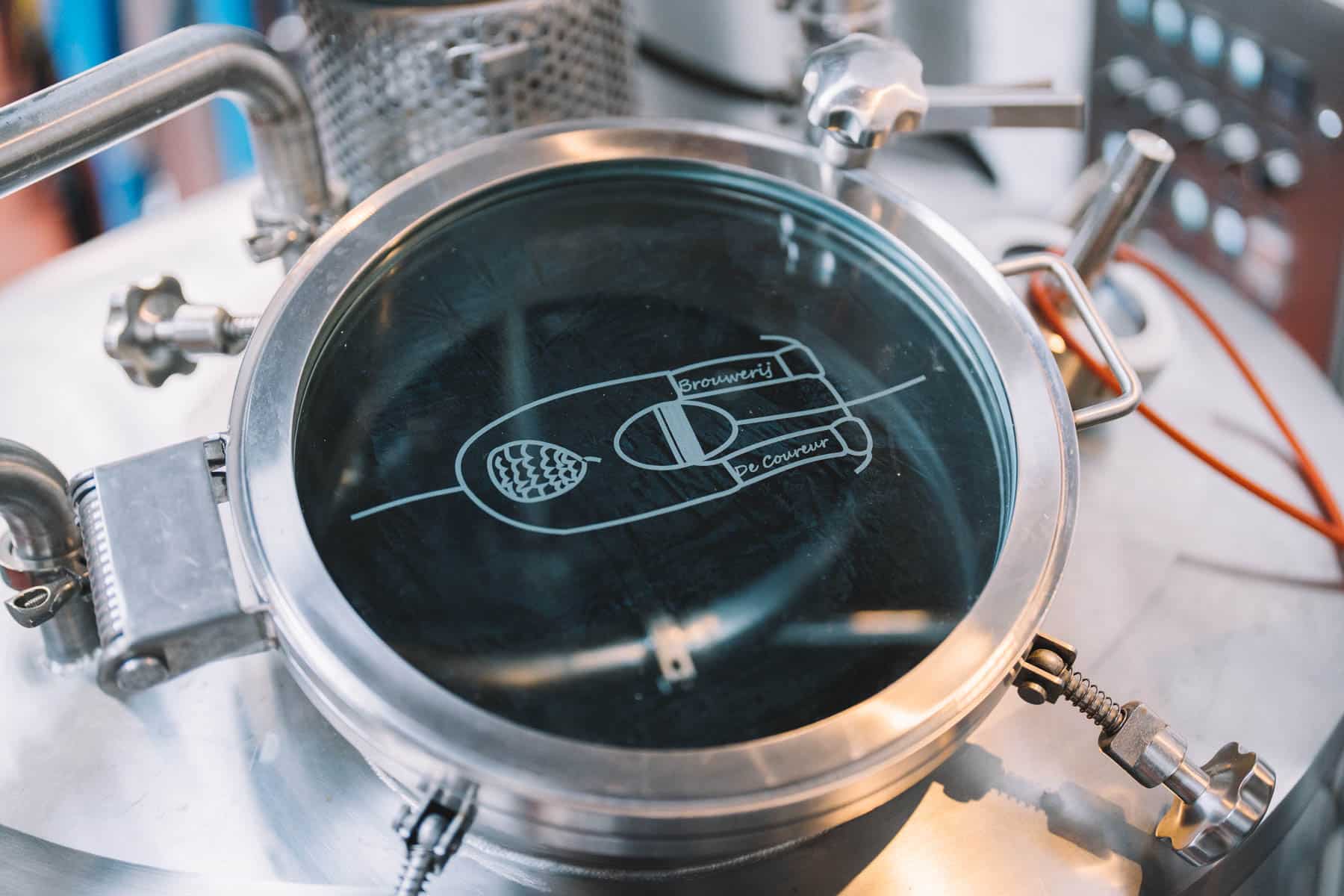

Eventually, they set up a two-kettle brewery system and four 5HL cylindrical conical fermentation tanks (and a bright beer tank) from NFE Machinery in China.They installed three horizontal serving tanks from Duotank in the taproom so they could pour fresh beer on draught, brewed and packaged less than 10 metres away on the other side of the same room.

Delvaux spent two years studying brewing at Syntra Antwerpen en Vlaams Brabant. Finally, they were able to secure the relevant permissions to brew from the food safety agency and excise authorities.

Their project was going to happen. They would brew their first beer on 1 April 2020, with family, friends, and people from the local neighbourhood all excited to be close to Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock to celebrate their achievement with them.

Brouwerij De Coureur was real. Nothing would stop them now.

VII.

TikTok

When the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020 derailed their plans for opening, they immediately turned to the growler. It was an idea inspired by their taproom experiences in the United States that they had always intended to implement, especially given their zero-waste policy.

Growler sales could never match the sales they’d expect from a full opening, but it was a positive start given the circumstances. In fact, they completely sold out all the growlers they ordered, and the initiative allowed them to get their beers into the hands of those in the neighbourhood interested in their project, many of whom were grateful for new experiences during the lockdown.

Everything at De Coureur pointed back to the humble bicycle. It was a bike accident that had led to their trip to Sawyer and their discovery of taproom culture in the US. Back in Belgium, they got around on their bikes, still refusing to buy a car. Their beers were named for cycling terminology—Colleke, Kuitenbijter, Souplesse. Their clientele would be arriving at the brewery on bikes. Their logo is based on an illustration by their 9-year old niece Lilia, a top down view of a cyclist in full flow.

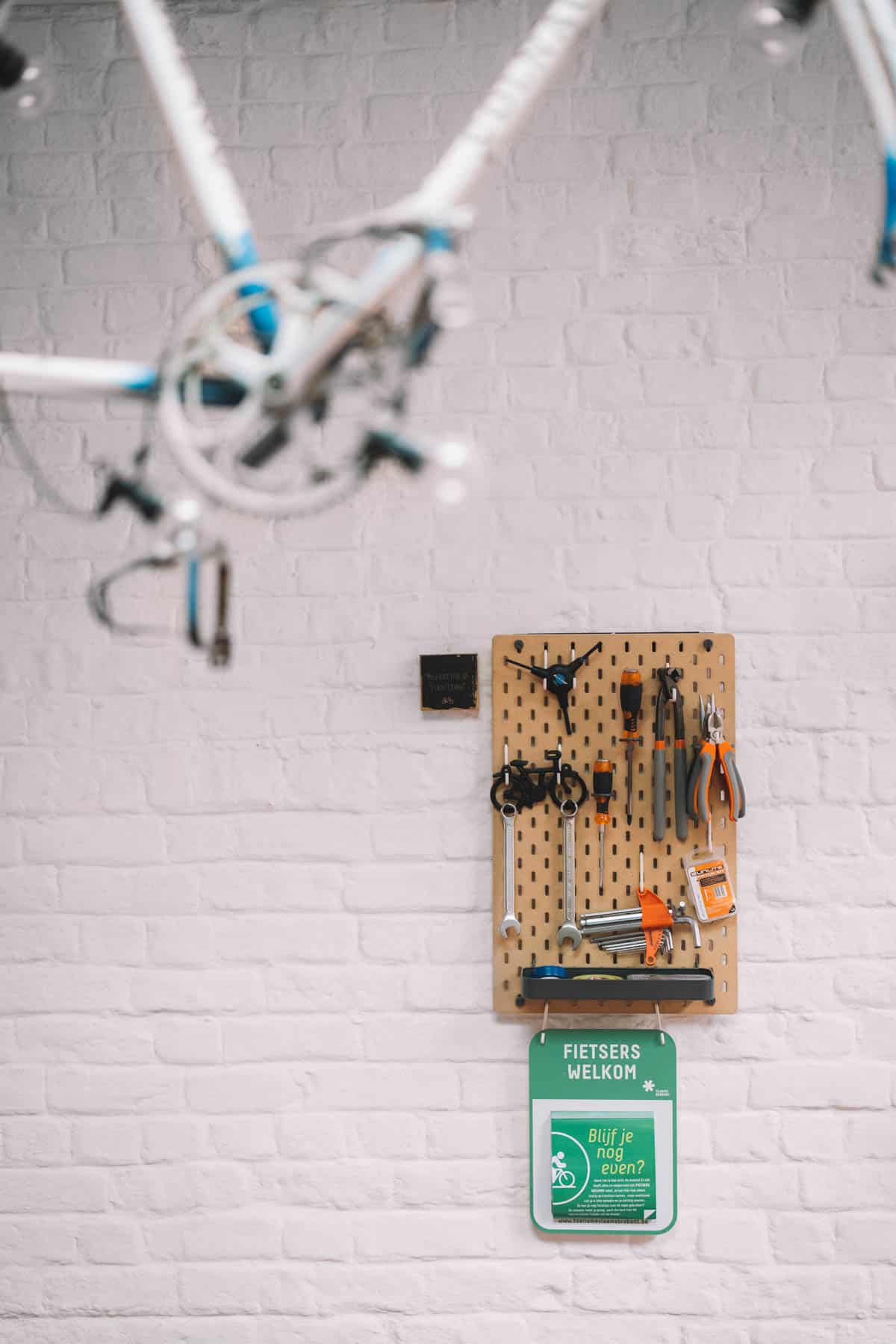

They contacted their local bike shop and asked if they could take any cycling paraphernalia that they were thinking of dumping or recycling.

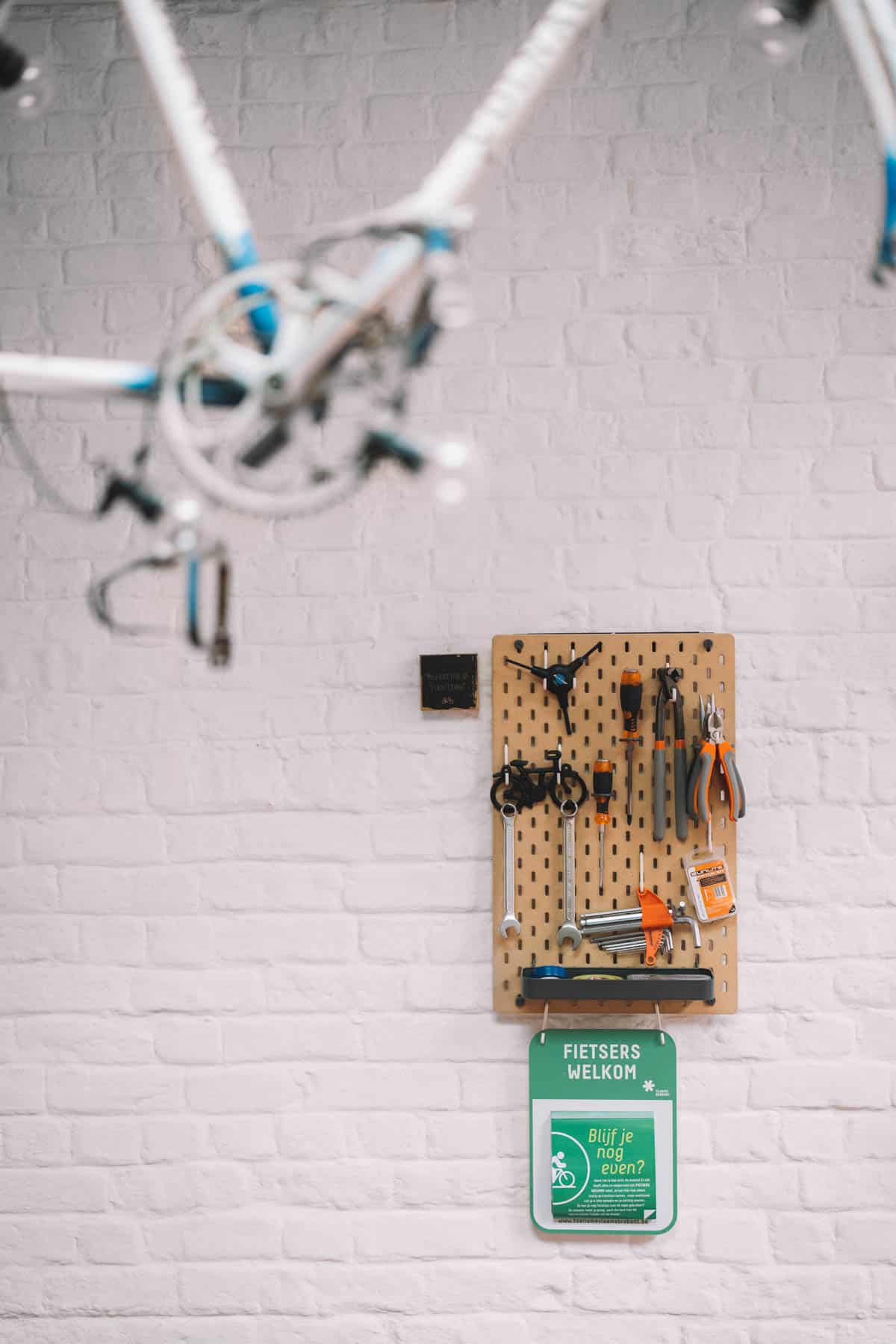

They secured old bikes, unique saddles, and strange wheels, and displayed them on the walls of the old Renault workshop that was now their brewery taproom. They found a series of newspaper articles from the 1960s and an old French cycling magazine, and displayed the clips on the wall of their back office. There are bicycle stands in the hallway entrance to the taproom. A line-up of bike saddles with handlebars attached like horns is displayed as if they are the trophy heads of hunted animals. Their tasting flight of beers is known as their “Peloton”.

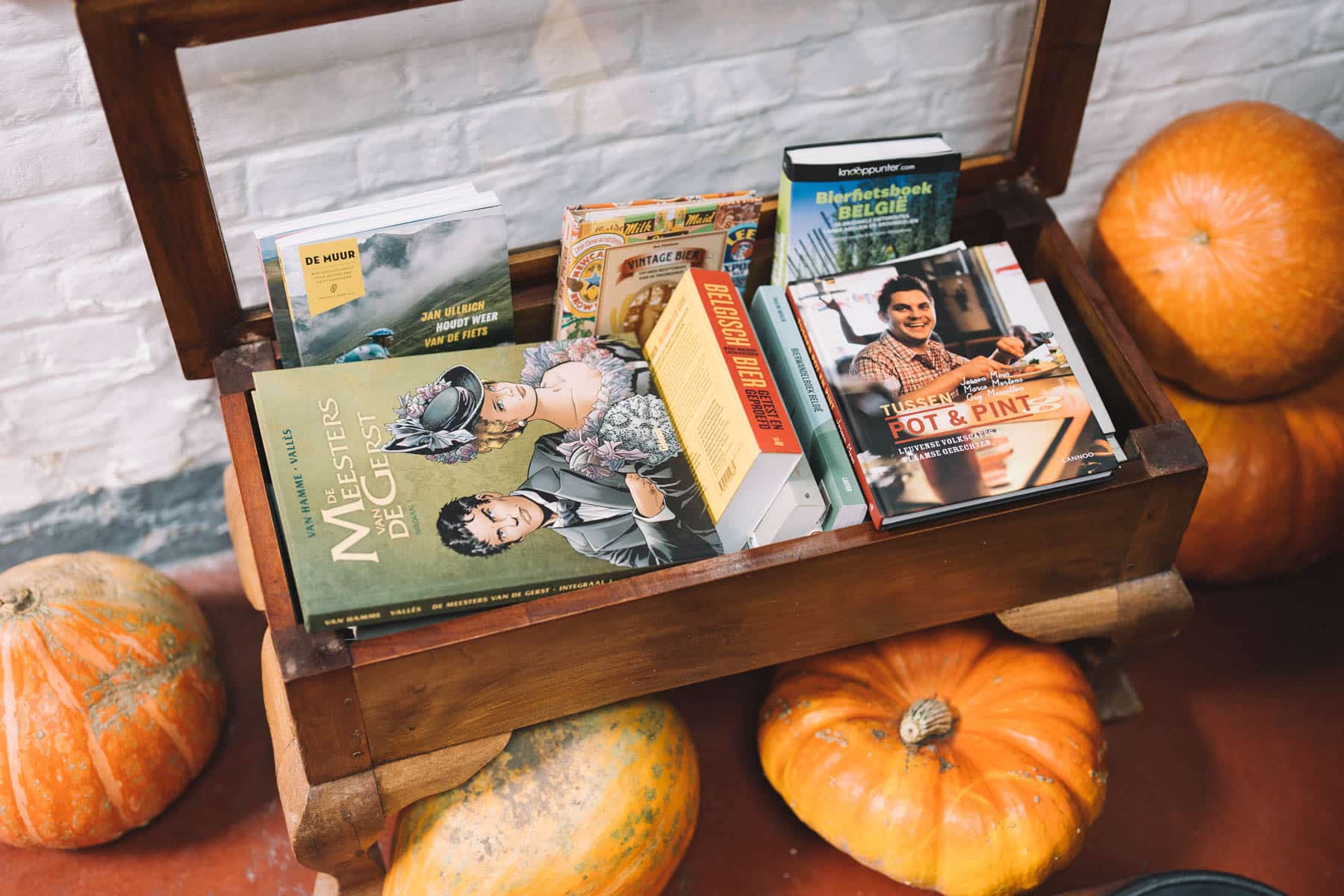

When De Coureur were finally permitted to open in mid-June of 2020, visitors sat on repurposed bar stools on which bike saddles had replaced seats, each decorated with cycling spokes. There were tricycles for small children. There were numerous cycling guides amongst a pile of second-hand books to read. You could buy De Coureur socks, complete with Lilia’s illustrated cyclist logo. One sign on the brewery wall read: “You lost me at ‘I don’t bike’.”

Ine Van der Stock opened a TikTok account. In matching lumberjack check shirts, monkey hats, and mouth masks, they danced to hip hop, sea shanties, and European techno. They paired mundane tasks in the brewery, such as purging yeast, with songs and memes popular on TikTok. Eventually, when the lockdowns were eased and people were welcome back into the taproom, they would involve their customers in their videos, with families and groups of friends carrying out TikTok challenges on the De Coureur account.

For one TikTok video, they even convinced other brewers from around Leuven to dance in their videos while visiting for a collaboration brew. Dimitri Staelens from Brouwerij Adept, Steven Bollion from Malterfakker and Brouwateljee, Luc Pauwels from Brouwerij Craeywinkelhof, and Jef Janssens from Hof ten Dormaal, among others, all danced enthusiastically to the instrumental hardcore trance track Sandstorm by Finnish DJ Darude, the brewers at first side-stepping, then clapping their hands, then raising their fingers into the air, and then jumping up and down as the song hit its climax.

Together, these brewers created a version of a beer from Pravda Brewery in Lviv to raise money for Ukranians fleeing the war. (Pravda—whose name translates as “truth”—decided to stop brewing during the war to make Molotov cocktail bombs with their bottles for the Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces). Pravda’s dry-hopped Golden Ale that De Coureur brewed with the local breweries was called Putin Huilo, commonly translated as “Putin [is a] dickhead”. De Coureur and the other breweries released their version of Putin Huilo at the Leuven Innovation Beer Festival earlier this year.

There was a sense of community about the beer—Leuven’s small, independent breweries coming together to do some good. Community as a core value would become central to the identity of De Coureur.

VIII.

Community

Delvaux and Van der Stock put in place small initiatives that embedded the brewery into the fabric of Kessel-Lo life: providing games for children to play, ensuring the space is as family friendly as possible, and donating to local charity projects. They learned their patrons’ names. They learned their patrons’ dogs’ names. “We inform them, listen to them, take them into account,” says Delvaux.

They hung repair tools on the wall so visitors could mend their bikes while they stopped at the taproom. And they put in place a “Pay it Forward” scheme, where visitors could buy a beer or set aside an amount of money, no matter how small, for friends (or strangers) to spend at the taproom. At any given time, there are between twenty and thirty “Pay if Forward” cards attached to a board beside the bar.

Now, with the lockdowns behind them, De Coureur’s taproom is full every weekend. Cyclists quench their thirst after a long ride in the hills around Leuven. Families play old café games that Delvaux and Van der Stock have piled up in the taproom. Pizza delivery staff shout through the crowd to find out which table has phoned in the Pepperoni pizzas. Sometimes, when there’s an international cycling tournament in town, like the World Championships that took place in Leuven in 2021, the taproom gets even busier.

For Bart Delvaux and Ine Van der Stock, living their dream on these days has meant long hours on their feet, with the tired legs of a “calf biter” ascent, but with the satisfaction of having climbed a steep rise and enjoying the freewheel downhill, riding—at least for now—“op souplesse”, totally at ease.

*