The Haspengouw region of gently rolling hills, charming villages, and fertile vineyards has been described as a “beer wasteland”, home to only a few breweries compared to other regions in Belgium. But there has been plenty of activity in the beer scene here in recent years. Just who are the people leading the Haspengouw beer blossom?

Words by Breandán Kearney

Photos by Ashley Joanna

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “Common Place” series. Read more.

I. An Unlikely Wasteland

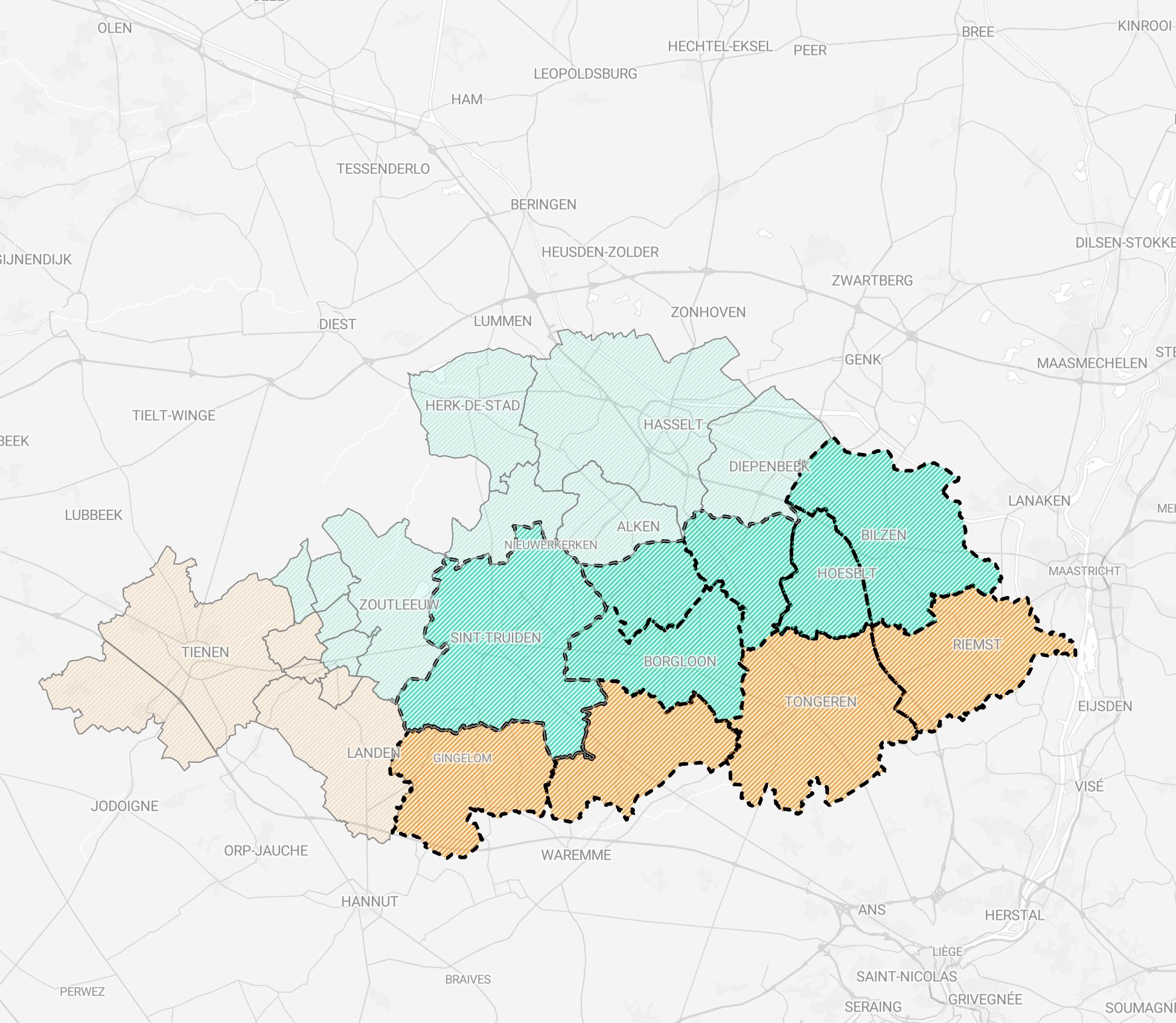

The Haspengouw, or Hesbaye in French, is a loamy plateau in Belgium between the Meuse and Scheldt rivers which stretches into four different Belgian provinces: Limburg, Flemish Brabant, Namur, and Liège. Its cultural heartland, however, is the region in Limburg south of Hasselt which extends from Sint Truiden to Riemst. The Haspengouw has been one of Belgium’s main agricultural regions since Roman times, and became a commercial fruit growing powerhouse in the second half of the 19th century as rail networks developed and industrial centres in England demanded apples, pears, and cherries.

On the face of it, the region’s rich food culture, agricultural prowess, and status as a tourist hotspot should make it a place with abundant options for beer. However, the Haspengouw is not highly regarded in Belgium for its beer scene. It doesn’t form part of the pilgrimage that international beer enthusiasts take to places like the Pajottenland, the Westhoek, or Henegouwen. It’s not home to a large number of breweries or famous cafés.

All green areas are “Vochtig Haspengouw” (“Moist Haspengouw”) and all orange areas are “Droog Haspengouw” (“Dry Haspengouw”).

The areas in more pronounced colour with darker outlines are considered to be the “Hoogstamregio” or “Standard Region”:—what most people refer to when they talk about the Haspengouw.

“I’m aware of only a handful of breweries that are there and I can’t get my head around why that is because throughout history agriculture has always come as a natural partner to brewing,” says Kristof Tack, who grew up in the region and who owns beer import business Gobsmack. “Haspengouw is a bit of a beer wasteland.”

Perhaps it’s because the fertile soil and gently rolling slopes here are more suited to growing grapes, and the emergence of wineries across the Haspengouw has stifled the production of other alcoholic beverages. Perhaps it’s because the people of the Haspengouw, living as they do in a rural environment, enjoy rather conservative tastes, with little need for more producers of beer than they now have. Or perhaps it’s because the slower pace of life has resulted in many young people from the Haspengouw moving to cities further west such as Leuven or Brussels, the very people who might ask for varied types of beer or who might embark on enterprises to brew beers which are different than what’s there today.

On the other hand, maybe there is a blossoming beer scene here, and it just takes some reading between the lines to see it.

II. Fruitless Endeavours

You might imagine that the fruit used in most of Belgium’s fruit beers would originate here, the country’s biggest fruit growing region. But that’s not the case. Raf Souvereyns of the nearby Hasselt blendery Bokke often works with Haspengouw fruit. In their Bloesem Bink, Brouwerij Kerkom use pear syrup which is produced in the village of Vrolingen. The cherries from the Liefmans Cuvée-Brut come each year from the Briffoz family kriek farm in the village of Jeuk. But these are the exceptions. Today, for various reasons, few breweries producing fruit beer in Belgium use fruit from the Haspengouw.

For example: When he was a child, long before he had his beer import business, Kristof Tack’s family cultivated around 70 cherry trees on a small plot of land, selling their produce at the Belgian Fruit Auction as many farmers did. In the mid-1980s, Tack noticed that Belgian brewers were no longer buying Haspengouw fruit from the Auction, and he asked his father why. His father suggested that the reason was the accident at the No.4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in what is now Ukraine. A swathe of Eastern Belgium was thought to be more affected than other regions in terms of potential contamination. There is no scientific evidence about the impact of the nuclear fall-out on the Haspengouw’s fruit production, but Tack points to changes in perception. “[My father] said after that, it was really hard to get any fruit sold from here,” says Tack. “Whether it was fear of contamination, whether it was actual contamination, or some dotted stocks that were contaminated, I don’t know.”

Another reason that krieken from the Haspengouw appear less in Belgian cherry beers is the increased import of sour cherries from Eastern Europe at lower prices. Luc Scheerlinck of the Limahof fruit farm in the village of Hoeselt has seen demand from breweries for his cherries decrease, largely due to the cheaper prices Belgian brewers can pay for cherries to be shipped from Poland. “At one time, there were more than one hundred kriek farms in the Haspengouw,” he says. “Now there are around five.” Scheerlinck points to higher wages, greater land prices, and costs relating to manual work compared to those of larger fruit growing operations in Poland and Czechia. “Within five years, it’s likely we ourselves won’t be able to grow krieken.” There’s a possible future, not too far away, where the Haspengouw fruit yield becomes an export product for juices and jams only and loses its historic connection to Belgian beer.

III. State of Affairs

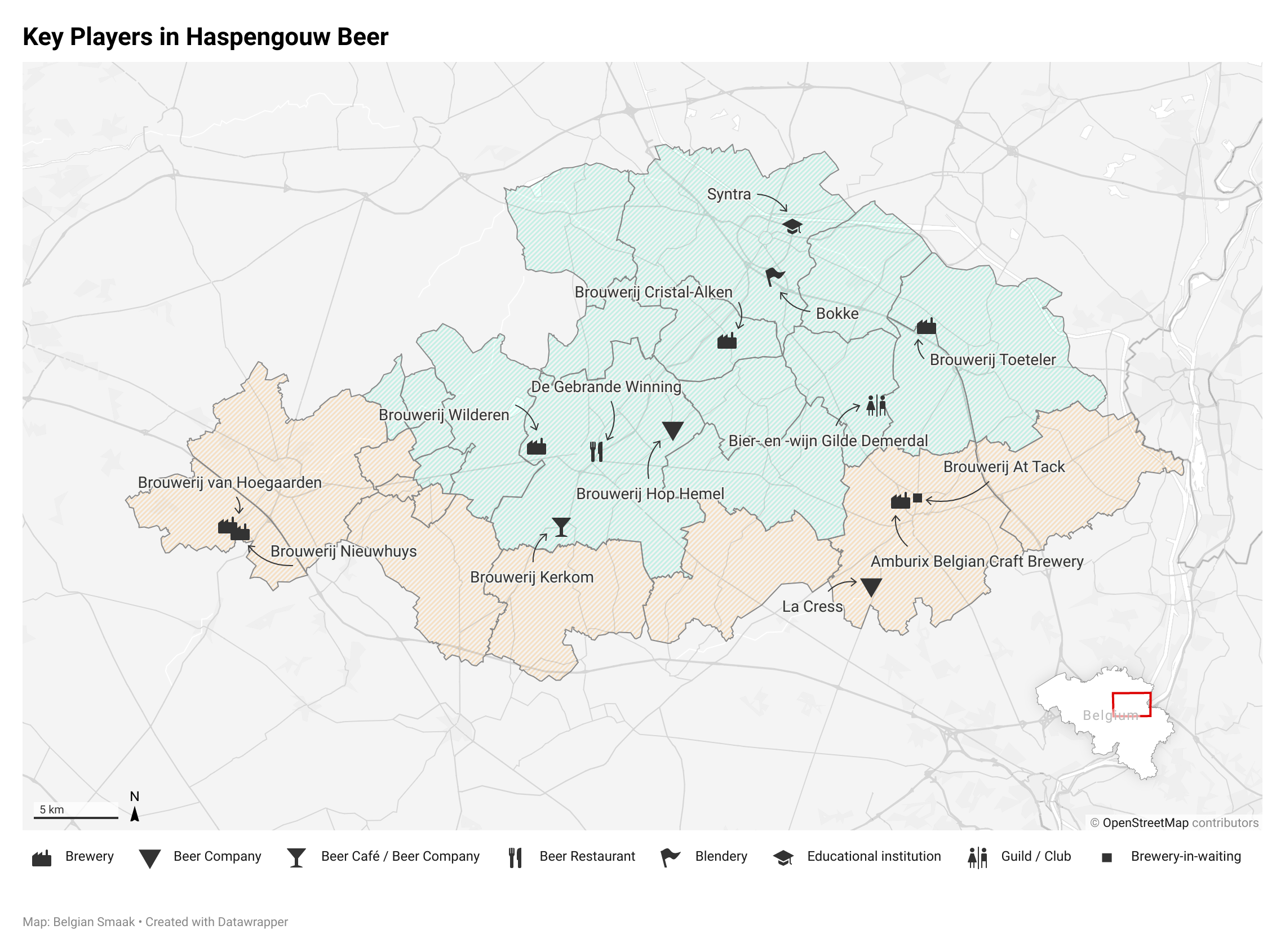

Steven Broekx is an architect and one of the Haspengouw’s most passionate beer enthusiasts. Following Broekx across the Haspengouw might afford us an insight into the beer scene here, as well as giving us an introduction to its most influential players in recent times, notably: prominent beer company and café Brouwerij Kerkom; international lager brewery Cristal Alken; and traditional producer of Belgian Ales, Brouwerij Wilderen.

In 2007, Steven Broekx got married to Wivina De Bus. Their wedding reception took place at Brouwerij Kerkom in Kerkom-bij-Sint-Truiden, a café and beer company which once housed a functioning brewery. It’s a beautiful place for a wedding. An old farm courtyard with cobblestones allows ample space for tables and chairs, and the frayed red brick and higgedly-piggedly roof tiles emanate an old-world romance. “We didn’t drink pintjes at our wedding,” says Broekx. “It was all Bink Blond.”

Kerkom has been a brewery on and off since 1878, but today the brewery system sits unused because of what owner Marc Limet says are issues with a permit. Currently the “Bink” range of beers—”Bink” is the nickname for people from the nearby city of Sint Truiden—are brewed not in the Haspengouw, but at Brouwerij Cornelissen in Opitter and at De Proefbrouwerij in Lochristi. For a few years after his wedding, Steven Broekx wanted to find beers produced in the Haspengouw, but it proved more difficult than he was expecting.

One beer which feels like it has always been produced in the Haspengouw is Cristal Pils, a lager which first appeared in 1928 and which Broekx remembers as being an ever-present on the family’s kitchen table during his youth. Cristal is produced by the Cristal-Alken brewery in the village of Alken, between Hasselt and Sint Truiden. In 1988, the Cristal-Alken brewery merged with Brouwerij Maes of Kontich-Waarloos to become Alken-Maes. It was then bought by Scottish & Newcastle in 2000, and eventually taken over by Carlsberg and Heineken in 2007.

“Cristal is basically famous for being the first modern Belgian Pilsner on the Belgian market,” says Sebastiaan De Meester, the Corporate Affairs Manager of Brouwerij Alken Maes. “Cristal is Alken. And Alken is Cristal.” Today, Steven Broekx’s children go to school in Alken. As they drive past every morning, his children remark on the red and white striped malt silos, referring to them as “popcorn bags.” Broekx respected the brewery—“Cristal is important for Limburg because, even now [that] it is owned by a bigger company, it still is ‘our’ pils,” he says—but he was looking for something other than lager.

Then in 2011, a new brewery opened in the Haspengouw village of Wilderen, 10 kilometres from Steven Broekx and Wivina De Bus’ home in Zepperen. The couple cycled to Wilderen on Belgium’s Open Monument Day, when protected buildings are showcased to the public. On the brewery’s terrace, they drank one of Wilderen’s first beers: the Tripel Kanunnik, a spicy four-grain Tripel of 8.2% ABV brewed using barley, wheat, oats, and rye, which today makes up about 40% of all beer the brewery produces. In pre-COVID years, Wilderen received around 100,000 visitors every year, the busiest months being April and May when the Haspengouw fruit trees are in blossom.

Brouwerij Wilderen is a brewery and distillery whose buildings date back to 1642. When current husband and wife owners Mike Janssen and Roniek Van Bree came across the buildings on the internet in 2007, there had been no activity on the site for generations, but they saw the potential of the location. “We arrived here and we signed a document two hours later,” says Janssen. Before Wilderen, Janssen worked as a commercial director at Brouwerij Riva in Dentergem, and he later set up Brouwerij Ter Dolen in Houthalen-Helchteren in Northern Limburg. “I have worked in every Flemish province,” says Janssen. “The Haspengouw is open. It is unique. It’s ultra beautiful.”

The courtyards and terraces and fruit trees surrounding Kerkom and Wilderen convinced Steven Broekx that beer in the Haspengouw could leave an impression on people. “You have to look for it,” he says. “That’s what makes the experience.”

IV: The New Generation

Steven Broekx began attending beer festivals, including Zythos and Bruges. Noticing his growing obsession with beer, some friends gifted him a homebrew kit for his thirtieth birthday.

Then, in 2012, Steven Broekx signed up for classes to become a “zytholoog” (“beer sommelier”) which were offered at Syntra vocational school in Hasselt.

The teachers of the two year Zytholoog course had contributed for years to Haspengouw’s beer scene: Yannick Boes and Robert Putman had been instrumental figures at the Cristal-Alken brewery; Nicolas Soenen worked at Duvel Moortgat before taking up his current position at Yakima Chief Hops; Andy Jans was a beer sommelier from Hasselt; and Kristof Tack’s cousin Karel Tack, originally a student, but soon teaching and developing parts of the course, even had plans to launch his own small brewery in the region. At Syntra in Hasselt, the Haspengouw’s past and present leaders were inspiring its future ones.

There was one empty seat available to Steven Broekx when he walked into the classroom at Syntra for the first time. It was to the left of Geert Vandormael, who had studied at a hotel school in Hasselt and in 2009, after five years of study, had become a Masterchef. Vandormael worked for Ford and then as a Logistics Officer at the East Limburg Hospital but had continued studying food, taking additional modules at the hotel school in vegetarian cooking and Asian food.

Seated side by side, the two men looked like polar opposites. Broekx was tall, with black hair and beard, and wore large-framed glasses. Vandormael was short, with a shaved head, and dark, brooding eyes. The pair struck up a close friendship, sharing a curiosity about the ways in which beer experiences are created. They made arrangements to go for some drinks in a café called Bier Punt in Diepenbeek after their final examination at the end of the two year course, inviting three other students in the class who were sitting around them: Bart Boes, Patrick Dubuc, and Didier Gaillard.

As the five classmates made their way through a few beers (mostly a hoppy ale called Ter Dolen Armand) on that May evening of 2013, they hatched a plan, one which involved hosting beer and food pairing events for people in the Haspengouw. Unlike many plans formed at a bar, they followed through. “We saw a hole that no-one was filling in Limburg,” says Vandormael. Less than a year later, in March 2014, the five classmates incorporated a company called the Brouwers Kwintet.

At the exact same time, a beer restaurant opened in the Haspengouw which would prove to be a huge source of inspiration for the Brouwers Kwintet. De Gebrande Winning (“The Burned Farm”) had been a restaurant in Sint Truiden for years, but when Owner Chef Raf Sainte took it over in 2014, his ambition was to get creative. He completely changed his menu and bierkaart, and began organising a regular beer and food pairing event for around 100 people in an old church in nearby Montenaken on the first Thursday of every month. Steven Broekx and Geert Vandormael began attending the beer club religiously, and they even hosted a cheese and beer pairing edition.

After only a few years of opening, De Gebrande Winning was named Belgium’s “Beer Restaurant of the Year” at the Beer Awards Digital Festival for three consecutive years, as well as securing a Bib Gourmand from the Michelin Guide, and receiving recognition from Gault Millau. The arrival of Raf Sainte and De Gebrande Winning on the Haspengouw beer and food scene completely inspired the Brouwers Kwintet. But now, it was time to create something of their own.

V. The Brouwers Kwintet

The Brouwers Kwintet started homebrewing together on the kit that Broekx had received for his thirtieth birthday. They would move around their five houses, brewing at a new location each time, focussing more on trying Geert Vandormael’s food offerings than on perfecting their brews. As a result, many of the beers did not turn out well. “By the end, we had made something,” says Vandormael. “But I think it was one of the worst beers we ever made.”

The Brouwers Kwintet hosted events anywhere that would have them and for anyone who would ask: at cafés and restaurants, but also in the kitchens of companies and in private living rooms. As the number of events mounted, the pairings became even more considered and ambitious. They paired smoked salmon mousse and dill cream with De La Senne’s dry, citrussy Taras Boulba; caesar salad, poached quail eggs, and grilled chicken with Het Nest’s bright Saison-esque Koekedam; and the rich, vinous Liefmans Goudenband with blue cheese, walnuts, jonagold, and mustard dressing.

Soon, they wanted their own beer to use at pairing events.

Their new beer was brewed at several locations, including a few times at Brouwerij Den Toetëlèr in Hoeselt, a small village to the north of Tongeren in the heart of the Haspengouw. One of the owners of Den Toetëlèr, Luc Festjens, had started the brewery in 2011 as a side project with some colleagues from local beer and wine guild, De Demerdal.

Den Toetëlèr’s beers are unique because in each one, Festjens uses elderflower. He replaces coriander and bitter orange peel with elderflower in his Toetëlèr Wit. He uses elderflower in his Toetëlèr Echte Kriek, buying cherries directly from the Limahof fruit farm. And he adds elderflower to the spices of his winter beer, Toetëlèr Speculaas. Den Toetëlèr is local dialect for elderflower, but it’s also the name given to a whistle made from the wood of the tree of the elderflower.

The Kwintet Tripel produced at Den Toetëlèr was used in a range of food pairings for the Brouwers Kwintet events. They found particular success in a pairing with Zander, a game fish which the Kwintet served with carrot butter and noodles. Their experiences with the Kwintet Tripel made them curious to brew more of their own beers. And so the five ramped up the homebrewing.

But coordinating the schedules of five different people, each with families, full-time jobs, and different visions for the project, became impossible. Bart Boes, Patrick Dubuc, and Didier Gaillard decided to take a step back. But Steven Broekx and Geert Vandormael were not ready to stop. They decided that they would continue brewing together, just the two of them, but this time in only one place, building out a small but functional 50 Litre brewing system. They converted one of the small barns in the courtyard of the old farmhouse in Zepperen where Broekx lived: a space 8 x 3 metres, with chipboard panelled walls, a concrete floor, and large stainless steel surfaces befitting a modern restaurant kitchen. Importantly, they installed a small bar and a long table to host beer and food pairing events.

VI. Hop Heaven

In May 2017, Broekx and Vandormael brewed a Pale Ale using only the piney, stone-fruit-esque Simcoe hop. Stuck for a name for the beer, they consulted the “druivelaar” hanging on the wall of their converted barn space, a tear-off, one page-per-day calendar which featured lists of Holy Saints under each of the days of the year. On that particular day, Philip Neri was listed below the date, a Saint known as the Second Apostle of Rome. “Every day has multiple Saints,” says Broekx. “It’s a never-ending source of names.”

The Philip Neri Single Hop Simcoe Pale Ale became the first beer of a new project: “Hop Hemel” (In English: “Hop Heaven”).

In August, they brewed another Pale Ale, but this time using only the pungent, herbal, Zeus hop variety, and they named it after Saint Monica, who wept every night for the reformation of her son. The following month, they brewed Hieronymus, a Black IPA using the Polish dual purpose hop variety Marynka, the beer named after a priest, theologian, and historian. Experimentation continued: In October, they brewed the Judas Thaddeus Quadrupel; Later, the Paus Simplicus Tripel. During the two years that followed, they nailed more than 50 recipes. It was time to introduce their beers to the public.

But the Haspengouw at the time did not feel like a place for new beer projects.

In January of 2019, one of the Haspengouw’s newest breweries—Brouwerij Amburon, located near Tongeren—was declared bankrupt. Amburon produced the Tungri beers, as well as brewing for third parties, and had been in operation for just two years before it was forced to close.

And then the local beer club, the Limburgse Biervrienden (Limburg Beer Friends), in existence for twenty-five years and boasting hundreds of members, took a decision to cease their activities for good. For years, they had been unable to convince younger generations to become members and no-one had come forward to lead the club. Now, they had little option but to end their association forever.

In the midst of all of this, Steven Broekx and Geert Vandormael burst into action.

VII. Business Plan

The Hop Hemel began hosting ticketed beer and food pairing events in Zepperen. Groups of beer enthusiasts would sit around the long table in the brewery space beside Broekx’s home and enjoy a range of interesting food combinations with the beers they had brewed: Innocentius, an Oak-Aged Mulberry Golden Ale, with a pearl onion tarte tatin; Lupus Blossom-Honey Braggot Saison with sticky spicy ribs; and their super-dry Brut IPA, Caesarius, with slow cooked pulled pork, pineapple salsa, and flatbread. On open days that they would host, beers sold out and food ran short. They began limiting their flights to 100 units.

In December 2019, Broekx and Vandormael assisted Raf Sainte in organising a large beer and food festival at De Gebrande Winning called the “Circus”, helping him design festival glassware and arranging the logistics of tents, tables, and chairs. The event featured interesting breweries from all over Belgium, the beers all paired with food. The Haspengouw was hungry.

As happens with successful homebrewing projects, friends, family, and commercial colleagues began asking Broekx and Vandormael whether Hop Hemel beers would become available to buy. Broekx and Vandormael travelled to the German city of Nuremberg to attend the BrauBeviale, one of the biggest trade fairs for the beer industry. They spoke to several manufacturers of brewery systems and requested a number of bespoke quotes. Back home, respected distributors such as Marlou Drankenspecialist in Zonhoven made enquiries about stocking their beers. Retailers like Bar Deluux in Pelt became interested in selling their products. Raf Sainte at De Gebrande Winning wanted to place some orders.

Broekx and Vandormael worked on a business plan to open a commercial brewery and they visited business advisors with experience of helping start-ups. There was very little that could possibly get in the way of their ambition, and nothing, they thought, that would force them to change their plans.

VIII. Pandemic

On 18 March 2020, Belgium went into Lockdown due to the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Not only were Steven Broekx and Geert Vandormael unable to meet up to brew together, to visit breweries, or to conduct beer and food pairing events, but their day jobs became especially demanding and intense.

As an architect focussing on residential properties, Steven Broekx found himself busier than ever. The Lockdown had shown people how important the spaces in which they lived were to their wellbeing. In the East Limburg hospital, Vandormael became responsible for getting hundreds of pallets of personal protection materials into departments of the hospital that needed them. There was a global shortage of masks, gloves, and protective clothing, and Vandormael had to figure out how to get them delivered to where they were needed.

Brewing and creating beer experiences was their passion, but the newfound challenges in their day jobs motivated them and gave them a purpose. This new perspective resulted in them taking a different approach, officially incorporating Brouwerij Hop Hemel as a company on 1 October 2020 with the firm intention of continuing as a part-time project rather than as their main occupations. As waves of COVID-19 infections rose and fell, and as government lockdowns tightened and eased, they began brewing when they could. But instead of 50 Litres in Zepperen, they brewed 500 Litre batches of beer at the Genk brewery BRAUW, a facility which allowed people to brew their own batches.

These batches included a Grape Ale called Geronimo, a Double Dry-Hopped New England Style IPA called Alexandra, and a Thai Russian Imperial Stout called Stephanos. The Hop Hemel beers now sit beside the Belgian Ales of Kerkom and Wilderen on the beer menu of De Gebrande Winning. “We want to be a little experimental,” says Vandormael. “I think what we’re doing is unique in Limburg.”

IX. Reading Between the Lines

On 8 May 2021, outdoor hospitality opened up again to drinkers in Belgium and on 9 June 2021, indoor drinking and eating was once again permitted. Kerkom and Wilderen are expecting to see a lot of people back on their terraces this summer, especially given that many Belgians are likely to holiday in-country due to strict international travel restrictions. Broekx and Vandormael are looking forward to getting back to delivering intimate food and beer pairing events with the Hop Hemel.

In recent years, Steven Broekx, his wife Wivina De Bus, and their three children, Malin, Linus, and Remus would often go cycling from their small farmhouse on the Terwouwenstraat in Zepperen to other villages in the area. One place they visited was an art installation near the village of Borgloon that had been created to fit into the landscape. The artwork was a church structure that stretched ten metres high and consisted of 100 stacked layers of steel plates which together weighed thirty tonnes.

The architects had designed the church so that you could see the landscape through the plates no matter where you stood, but how much you could see and what you saw depended on where exactly you were standing. The artwork was titled “Reading Between the Lines” and had become one of the Haspengouw’s most iconic visitor attractions.

De Bus and Broekx’s children would try to climb the interior. In the evening, the setting sun would cast their figures into silhouettes as the orchards lit up under a yellow and orange glow.

As an architect himself, Broekx appreciated the experiment in perspective.

Wandering around the artwork, he found some spots from which he could hardly see the church at all. The steel frames appeared as dots, almost like birds or insects dispersing, the fields and orchards clearly visible through the art as if the construction had dissolved into the landscape.

From other spots, however, only a few metres away, the church was completely visible, its walls and roof dominating the view towards Borgloon. It was all about point of view.

How you see things is not just about accepting what does or does not appear to be there, but it’s dependent on the place in which you’re standing. Change your focus and a whole set of new colours might just blossom right there in front of you.

*