The Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 was one of the most horrific tragedies of the First World War. Do beers which use the battle in their branding constitute a tribute to those that fell? Or is the brewery that produces them using a tragic event as a cynical tool for commercial gain?

Words and photos by Breandán Kearney

Edited by Oisín Kearney & Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

This editorially independent story has been supported by VISITFLANDERS as part of the “War Chest” series. Read more.

Eric Deprez wants to show me the toilets. He leads me down into the reconstructed First World War dug-out at the Memorial Museum in the village of Zonnebeke. Eric tells me that while it feels as cramped and as dark and as basic as the dug-outs of 1917, I should also try to imagine the “crying of the wounded, the smell of death, and the artillery bombardments above ground which made it feel like you were moving on a ship.”

The toilets he points out are essentially wooden benches with holes in them placed in a narrow corridor where soldiers would have sat in long lines very close to each other while doing their business. They had to wait for gaps in artillery shelling above ground to empty the contents of those toilets, effectively “shitting on shit” until further notice, often for long periods. “A lot of boys became crazy after a few days in here,” says Eric.

The Battle of Passchendaele was a World War One military operation which took place between July and November of 1917 during which the Allied forces attempted to take control of the strategically important ridges to the south and the east of the city of Ieper which were being held by the Germans. During the months of that battle, hundreds of thousands of soldiers from across the world lived and fought on open fields of porridge-like mud around the village of Zonnebeke outside Ieper. The Battle of Passchendaele has become an international symbol of the futility of war. In 100 days, almost 600,000 soldiers were killed for a gain by the Allies of only eight kilometres of ground. “In a small area, it’s enormous, that kind of loss,” says Eric. “That’s why they call it the Great War.”

Eric Deprez is a guide for Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck, a large family brewery in Izegem who produce a range of beers whose branding references the Battle of Passchendaele—Passchendaele Blond (4.8% ABV), Paschendaele Porter (5.7% ABV), and Passchendaele Ginger White (4.5% ABV). He tells me stories that he knows will capture my imagination. He tells me that before the first ever gas masks were invented in 1915 to protect against German chlorine gas attacks in Flanders, soldiers urinated on rags and towels and put them around their heads. They believed the ammonia in their urine would protect them from the greenish-yellow clouds that infiltrated soldiers’ eyes, noses, lungs and throats. Chlorine gas kills by asphyxiation. The trick worked, not because urine neutralises chlorine, but because chlorine dissolves in water and couldn’t pass through the wet, urine-stained cloths on the faces of the soldiers.

Eric tells me about how the French soldiers began by wearing flamboyant colours at the start of World War One, as they would have done for identification on the battlefield in the Napoleonic wars, but made themselves targets as artillery became more sophisticated, changing over to less colourful uniforms after experiencing huge losses of life. And he tells me about the cultural differences between the various nationalities, such as how the British troops never directly communicated with ranks far above them while Australian troops would drink beer with their commanding officers without any breakdown in respecting the chain of command.

In taking me around the museum, Eric speaks so knowledgeably about the details of war—the structure of regiments, military strategy, the various equipment used—that it soon becomes clear he himself has served in the army. I learn that Eric is retired Special Forces, having spent most of his career in the 1st Parachute Battalion, an elite fighting force in the Belgian Land Component often described as the “Belgian Paracommandos”. But he seems reluctant to discuss the details of his own service.

We pass a space at the doorway of the reconstructed dug-out which would have been used by medics to assess injured soldiers coming in from the battlefield. Those deemed fit enough were ushered away from this area as quickly as possible so as not to see their suffering colleagues. I ask Eric if he has experience of this. “It brings back some memories,” he says. “The best you can do is say to the boys to stay away from it, because seeing wounded friends is not good for the mind. We will see it when we are back behind the lines. Then we can have a discussion. But now you have to focus on the mission.”

Top right: Royal Field Artillery gunners hauling an 18-pounder field gun out of the mud near Zillebeke. Photo taken by John Warwick Brooke on 9 August 1917 during the Battle of Passchendaele. Photo in public domain. More info here.

Bottom: Soldiers of an Australian 4th Division field artillery brigade on a duckboard track passing through Chateau Wood, near Hooge in the Ypres salient. Photo taken by Frank Hurley on 29 October 1917 during the Battle of Passchendaele. Photo in Public Domain. More info here.

On behalf of the brewery that produces the Passchendaele beers, Eric has agreed to take me around the World War One sites around Zonnebeke so I can understand the context of their branding, but each time I bring up his own time in the army, he beckons me to move on to the next part of the museum, to the next village on the route, to the next cemetery on the tour.

The question that’s in the back of my mind is whether the Passchendaele beers are an act of remembrance by a brewery located only a few kilometres from where the tragedy of this battle unfolded or a cynical attempt by an ambitious business enterprise to commercially exploit the heightened interest in World War One since the centenary commemorations of 2014-2018. I’m hoping that Eric Deprez can help explain to me why Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck has decided to brand these beers using one of the most tragic events to have taken place on Belgian soil.

Afew weeks after our visit to the Memorial Museum in Zonnebeke, Eric Deprez leads me into Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck, an impressive fortress-like structure that looks more like a Flemish prison than a stately château. It’s a period earlier this year between the Spring and Winter national Covid-19 Lockdowns in Belgium so my body temperature is recorded automatically by a thermal imaging camera in the reception and I am required to sign in, wear a mask, and disinfect my hands before being allowed through the security entrance. As I clamber with my camera and sound gear, Eric offers to carry my audio recorder so we can move more efficiently, leading the way in his off-white t-shirt and dark green knee-length shorts, key-chains dangling at his side for quick deployment as needed.

The staff I meet—Commercial Directors Frederic Boulez and Marc Shrauwens, both of whom worked for Anheuser-Busch InBev before joining Van Honsebrouck—practice social distancing, and interviews are conducted across the length of a large conference room, surfaces cleaned and disinfected behind me as Eric ushers me through different parts of the brewery. Things have been thought out and executed in response to the pandemic here. Van Honsebrouck is a well-organised and professional outfit.

The history of Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck dates back to 1865 when Amandus Van Honsebrouck, the mayor of the village of Werken, operated a brewery and distillery on his dairy farm. In 1900, his son Emile opened a commercial brewery, Sint-Jozef, becoming one of two breweries outside the Payottenland to produce Lambic. In 1953, the name was changed to the family name: Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck. In 1986, the Van Honsebrouck family bought the Ingelmunster Castle, a stately home on the Stationsstraat which is depicted on the brewery’s logo and which gave the brewery its current name: “Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck”. This month, the brewery is reflecting on its long history after former owner Luc Van Honsebrouck passed away, aged 89, on 9 November.

In 2016, current owner Xavier Van Honsebrouck—Luc Van Honsebrouck’s son and the seventh generation of his family to run the brewery—closed the doors of their Ingelmunster brewery in favour of the new, purpose-built, state-of-the-art brewery I am visiting today. The new brewery has twice the brewing capacity of their previous facility at 25 million litres per year and the capability of producing Lagers and Ales, as well as beers of mixed and spontaneous fermentations. The new site took two years to finish and cost 45 million euros. They named it the “Bier Kasteel”.

Top right: Marc Shrauwens, Commercial Director of Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck, with a Passchendaele Blond

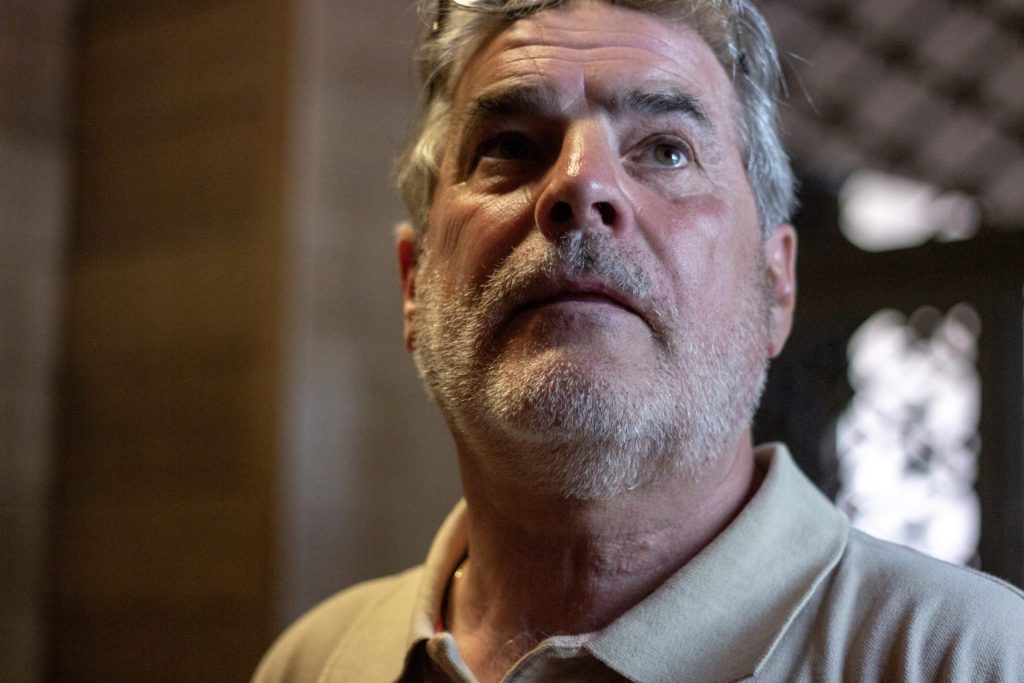

Bottom: Eric Deprez in the offices of Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck.

Eric Deprez started working here after retiring from the army because of his close friendship with owner Xavier Van Honsebrouck. During the visit, he shows me around all three storeys of the brewery, including the production facility, visitor centre, restaurant, event venue, and shop, all of which are surrounded by a central courtyard. He guides me as a soldier would, efficient and purposeful in his movements. He helps me tidy up my camera and audio gear after interviews. I have never seen my microphone cables rolled up so quickly, so tightly, so perfectly.

Eric shows me the large system in which Van Honsebrouck’s ales are brewed—their Kasteel range of Abbey-Style Ales (Blond, Rouge, Donker, Tripel, and Hoppy); their 8.5% ABV Belgian Golden Strong Ale, Filou; and their 9% ABV Belgian Strong Blonde Ale, Brigand. I see the large foeders where their mixed fermentation range of Bacchus Oud Bruin beers are matured in oak. And I’m brought to the top floor where their St. Louis range of Lambic beers are inoculated for spontaneous fermentation in a large shallow coolship bath. Several old wooden ceiling beams from the previous brewery in Ingelmunster have been added to the roof of this inoculation attic in a supposed attempt to recreate the microbiological environment of the previous space.

The Passchendaele brand is a newer addition to their line-up. In 2013, the brewery was developing a new beer with well-known Belgian brewing consultant Filip Delvaux. The objective was to create an ale with an alcohol content of around 5% ABV which had the drinkability of a Lager, but with a fuller flavour. At the same time, the Municipality of Zonnebeke, which is responsible for the village of Passchendaele, were seeking to collaborate with a brewery on a Blonde beer for the centenary commemorations of World War One between 2014 and 2018. A partnership was formed which involved part of the proceeds from the sale of the Passchendaele Blond being donated to the Municipality, Stad Zonnebeke. “It’s not like some other commercial hypes that pass by,” says Commercial Director Frederic Boulez. “We refund a part of the profits back to them so they get extra budget to organise remembrance events.”

Top right: The Passchendaele Porter (5.7% ABV)

Bottom: The bottle label of the Passchendaele Blond (4.8% ABV)

Van Honsebrouck delivered on their brief for the Passchendaele beers. They are technically flawless and exhibit Belgian balance in their construction, well-suited to war tourists who want to try something different, or locals around Zonnebeke seeking a meaningful alternative to their usual beers. My thoughts are that the hardened beer enthusiast may consider them pedestrian, the Blond perhaps a little too spicy and too sweet in the finish, the Porter not full or chocolatey enough, the Ginger White too subtle in its ginger additions. You get the sense that each could be deployed usefully by Van Honsebrouck as a base recipe for third party contracted beers as seems to be the case in Michelle’s Pub & Brasserie, the bar and restaurant inside the Bier Kasteel managed by Xavier’s Van Honsebrouck’s daughter, which serves its own “Michelles” beers—a Blond (4.5% ABV), Wit (4.5% ABV), and Porter (5.7% ABV). And while the Passchendaele range makes up only a small part of Van Honsebrouck’s production, it fills an important gap in their portfolio when it comes to beer styles and brand.

The description of the Passchendaele beers on the brewery website include assertions that “with every sip, we reflect on the horror of the Great War.” On the label of the beer, a red poppy at its centre, there’s a statement that it’s “The Great Beer”, together with a call to action in italicised text: “When opening a bottle of Passchendaele, please hold a minute’s silence to commemorate those who fell on the battlefield.” Van Honsebrouck is aware of the potential insensitivity of their branding, particularly in geographical markets with closer experiences of the First World War. The British, for example, lost 240,000 soldiers in just 100 days at the Battle of Passchendaele. “The UK is difficult,” says Commercial Director Mark Schrauwens. “They’re afraid to mix up the selling of such a product with wounds that haven’t healed or the remembrance of the people that were killed.”

It turns out that there haven’t been any donations from the brewery to the Municipality of Zonnebeke since 2018 when the formal WWI centenary commemorations finished. Boulez says that the collaboration with Zonnebeke ended “as planned” at the end of 2018 and prefers not to give details of the percentages or amounts involved out of respect to the Municipality. Various contacts at Stad Zonnebeke were unable to furnish more details to me about the amounts donated during the centenary commemoration period. Today, all profits generated from sales of the Passchendaele beers go to Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck.

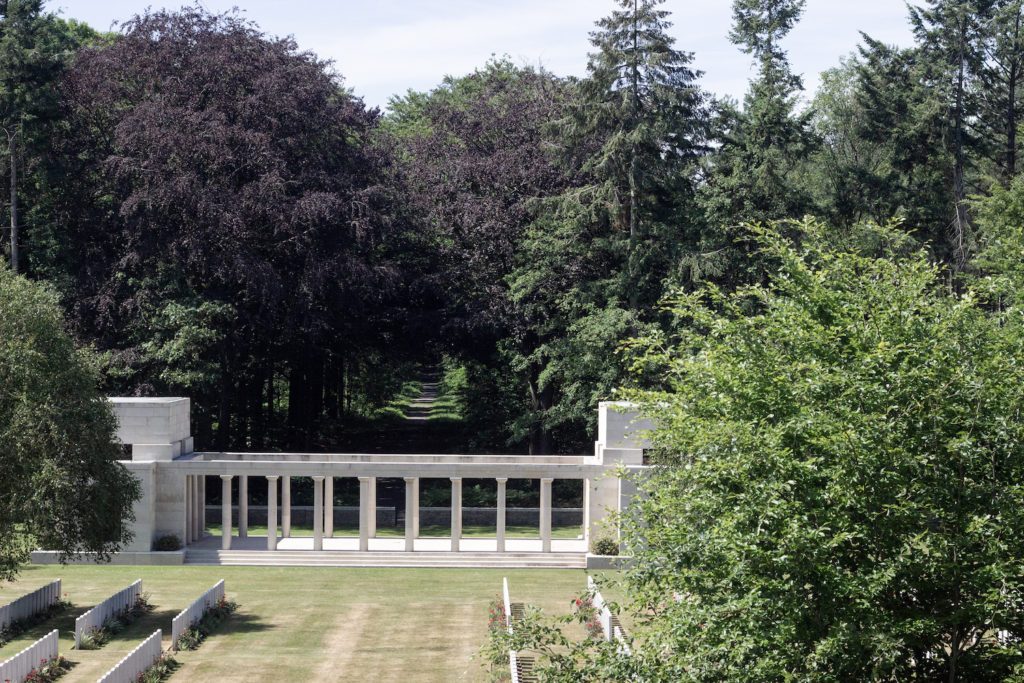

Eric Deprez leads me into a 70 hectare forest just outside Zonnebeke, telling me as we enter to stick to the paths because mines and ammunition from the First World War remain scattered across the ground. It’s another day and Eric is showing me around some World War One cemeteries, now dressed in a camouflage field jacket and jeans. We’re in Polygon Wood, the location of a scene of events during the Battle of Passchendaele which resulted in 20,000 Allied casualties and 13,000 German casualties in just one week, between 26 September and 3 October 1917. The Buttes New British Cemetery is located in the middle of the forest, with the headstones of dead soldiers facing towards the headstone of their dead Battalion Commander, as if standing to attention for morning inspection.

Polygon Wood changed hands between Germans and Allies many times, strategically important for its access to routes into Ieper. Today it’s a scene of tranquil beauty: the midday light is breaking through the 523 tall trees which surround the white headstones, colourful flowers peppered around the forest. But during the week of the Battle of Polygon Wood in 1917, it would have been a flat wasteland of mud, shrapnel, and corpses.

The British were the first to take the lead during the Battle of Passchendaele, launching attacks which were stifled by strong German resistance and heavy rainfall. New troops from the “Australian and New Zealand Army Corps” or ANZAC were deployed to get the offensive going again, but they too became exhausted and were eventually replaced by the Canadians who finally took Passchendaele. The Buttes New British Cemetery in the middle of Polygon Wood contains the remains of many of these Allied soldiers—British, ANZAC, and Canadian—the majority of whom are unidentified. The graves are marked: “A Soldier of the Great War”. Written underneath: “Known Unto God”.

In one of the advances during the Battle of Passchendaele, the New Zealand division lost 2,700 men one day. “It’s marked in New Zealand as the saddest day of the country’s whole history,” says Eric. Every single year on ANZAC day, the 25 April, there’s a service at 6am in Polygon Wood to commemorate that loss. Candles are placed on each of the graves and visiting Kiwis perform a Haka in the centre of the forest. Eric Deprez is in attendance every single year.

Eric brings us to a small cafe on the western edge of Polygon Wood, Café Taverne de Dreve. A “dreve” is a tree-lined avenue that passes through a forest. Inside, there are Australian flags hanging on the wall and commemorative posters of the WWI Anzac campaign in Gallipoli. The few older Flemish clientele there, outside and socially distancing, are all nursing a beer called Brothers Blond, so we order one too, a Belgian Blond Ale of 6.6% ABV and the café’s most popular beer.

The proceeds of sales of Brothers Blond go to the building of the Brothers in Arms Memorial located behind the café which commemorates those families who lost multiple children during the First World War. The work on the Memorial still has some way to go, and there’s no information about what percentage of proceeds from the Brothers beer goes to the building work.

We meet the café owner, Johan Vandewalle, who took over the café from his father and who spends most of his free time on archaeological digs in the area. Vandewalle, a grey-haired man with a thick moustache, is known locally as “The Mole” and has published books on his finds. He even appeared on an episode of BBC’s popular TV show “Time Team” as the local contact on a WWI dugout dig in 2008.

It turns out the Brothers Blond is actually just an existing beer with a different label, the Queue de Charrue Blonde which is brewed at another brewery—Brasserie Dubocq in Purnode—for well-known distributor Vanuxeem. The brewery has facilitated the arrangement to help raise money here for continued work on the Memorial. The Brothers reference has its origins in an incident in 2006 when human remains were discovered next to the café during the laying of a new gas pipeline. Johan “The Mole” Vandewalle was called to investigate. He confirmed from experience that the remains belonged to those of a World War I soldier and contacted the police and the Mayor of Zonnebeke to get a greenlight on an excavation.

After clearing the grave, Vandewalle and his team noticed another body, and then another, and then two more. In total, five bodies were exhumed, all Australians: the “Zonnebeke Five”. The last body, that of private John Hunter, had not been thrown in the grave like the other four bodies, but rather had been carefully laid to rest. Vandewalle was moved by the discovery, telling me about the moment he uncovered John Hunter’s head, which was wrapped in his ground sheet, and about the connection he felt to this soldier who died next to his café at Polygon Wood one hundred years ago. After research, including a trip by Vandewalle to Hunter’s family in Brisbane, it was confirmed through DNA testing and verbal accounts that John Hunter’s brother Jim had buried him just outside Polygon Wood during the War before he had returned to Australia.

Bottom: Johan “The Mole” Vandewalle, who owns the Café Taverne De Dreve, drinks ice-tea as the four customers at the table all drink Brothers Blond (6.6% ABV).

Lyrics from the Dire Straits song, “Brothers in Arms” are displayed on an unfinished plaque at the memorial site, together with an enlarged illustration which Vandewalle has created of Jim Hunter, holding his brother John Hunter in his arms before laying him down to rest. I tell Vandewalle about my mission to find out more about beers which use war in their branding. “Before the boys went into the trenches, they had to share a drink or a cigarette,” he says. “It’s not about business. It’s the way to pay your respects.”

I’ve heard this argument from Eric too, that it’s very natural to have a beer remembering the soldiers because one of the few things they enjoyed doing when they were behind the lines was drinking beer with one another. At the end of tours, Eric usually brings visitors to Menin Gate, a memorial at the eastern exit of Ieper dedicated to British and Commonwealth soldiers whose graves are unknown. At 8pm every single night since 1928, a brass band plays the Last Post bugle call. Before the centenary celebrations began in 2014, only a few people showed up to watch. Now it is usually packed with hundreds of people every evening. “Being at the Menin Gate is very emotional,” says Eric. “But when it’s finished, I’ve got my tears and nothing else. Drinking beers brings us together.”

We finish our beers at Café Taverne De Dreve and Eric Deprez leads me away to the next part of the tour. He’s now more open to discussing his time in the army, and over several hours, across a few more cemeteries, I’m able to question him in detail about what it was like to be a Belgian Paracommando and gradually build up a picture of what he’s seen in his own service. In particular, he tells me about one mission, the memories of which have stayed with him.

At 10pm on 19 May 1978, Eric Deprez landed in a Lockheed C-130 Hercules military aircraft at Kolwezi airport in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, on a mission with the Belgian Paracommandos. The city of Kolwezi is ore-rich and strategically located, and had been invaded by rebels from the FNLC (Front for the National Liberation of the Congo) who wanted to take control of the country from Zairean President Mobutu. After conquering the city, these FNLC rebels had taken hundreds of Zairians and Europeans hostage.

French paratroopers had already dropped into Kolwezi and were engaged in violent firefight with the rebels in a bid to secure the city. The morning after the Belgian drop, Eric’s Paracommando battalion travelled 6 kilometres by foot from the airport into Kolwezi, tasked with evacuating European citizens, mostly French and Belgian families, who had been working in the city’s mines and hospitals.

As Eric and his colleagues walked into a gutted Kolwezi lacking water, electricity and food, they were confronted with the remnants of a rebel massacre: bodies of 60 Europeans and 100 Africans—men, women and children—lay scattered inside buildings and on the streets. In some cases, their bodies had been blown apart by grenades. In other cases, they had been riddled with machine gun bullets. Some had been dismembered. Those that had survived just wanted to get out.

The Belgian Paracommandos were well-prepared and highly-trained. Eric and his colleagues evacuated 2,200 Europeans and 3,000 Africans, many being flown within hours from Kolwezi to the airports of Brussels and Paris. Initially ordered to leave after 72 hours, the Belgian Paracommandos ended up staying over a month to supply the local population with food and to maintain order. For Eric, it was one incident in a military career which spanned 17 years.

Eric Deprez has seen the horror and cruelty of war up close. He has studied military history, including that of World War One. And for years, he has paid his respects at the sites he is showing me today, where hundreds of thousands of soldiers died in the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917. Few others are as well placed to answer questions about the nuance of remembrance.

Just a few hundred metres from Johan “The Mole” Vandewalle’s Café Taverne de Dreve is a second cemetery. The Buttes New British Cemetery sits in the middle of the forest, but the Polygon Wood Cemetery sits just outside it. One headstone in this second cemetry stands apart from the others, shaped flat at the top rather than the curved headstones of the Allied graves. There’s a large crack three quarters of the way down the gravestone. An attempt has been made to fix it. The inscription on the headstone tells us it’s the grave of a low-ranked German infantry soldier called Hans Bogner. Although thousands of German soldiers died at the Battle of Polygon Wood, it’s the only German grave here in this cemetery. The others are buried in graves specifically for German soldiers at four villages nearby, maintained by the German War Graves Commission. But the exception here, the one German grave amongst those of the Allies, is intended to be a symbol. “It’s to show that in death, everybody is the same,” says Eric.

I ask Eric about the crack in the headstone and he tells me that it had been deliberately destroyed by unknown vandals a few years ago. “They come to do that by night,” he says, shaking his head. “That boy didn’t ask to come over here. Don’t destroy anything. Leave it. If you don’t want to see it, don’t come.”

Eric drives me to Langemark, 7 kilometres from Zonnebeke. It’s the location of one of those four German cemeteries. The others are in Vladslo, Hooglede, and Menen. There’s a feeling in these German cemeteries which is unlike that of the others we have visited. Large oak trees—the national tree of Germany—loom solemnly over the graves.

Eric tells me the three ways in which the German cemeteries are different to the Allied ones. Firstly, no German soldier has their own grave. They are buried in groups. “It was to humiliate the Germans,” says Eric. Secondly, there are no flowers. Whereas the Allied cemeteries have sections full of well-kept flower beds, there is nothing here but the oak trees. Thirdly, while the Allied headstones stand upright, a symbol of victory, those in the German cemeteries are all resting flat on the ground.

Eric points to a wall at the entrance to the cemetery which lists the names of three thousand German students who were taken from universities to fight for the German empire and who now lie here in graves. He takes me to a patch of ground near the entrance to the cemetery which measures no bigger than the small back garden of a terraced house. It’s a mass grave known as the “Comrades’ Grave” and contains the bodies of 25,000 soldiers, including that of German Flying Ace, Werner Voss. A sculpture of four mourning figures stands guard over the fallen.

Bottom: A sculpture of four mourning figures stand over the unmarked “Comrade’s Grave” at Langemark, which contains the bodies of 25,000 soldiers.

Over the years, Eric has taken German visitors to these cemeteries. Older Germans came on their own, or in small groups, and observed the toll the war took on their grandfathers, largely in silence. Younger Germans now visit in larger numbers, eager to see where their great grandfather is buried. Eric tells me that they usually sing, and that it’s almost always one particular song: “Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden”, known in English as “The Good Comrade”. In its recorded form, solemn brass band and male choir, it’s stirring and emotional, the words telling the story of a soldier who sees his friend die horribly by his side as they run into battle. Sung unaccompanied by young Germans under the heavy silence, foreboding oak trees, and dark headstones lying flat on the ground across Langemark cemetery—in a timbre of defeat and shame and mourning—I can only imagine how sad it must sound.

The emotion of the day begins to take its toll on me. During World War Two, the ship in which my grandfather Jimmy Kearney served was hit by a German submarine. Most of the crew drowned. My grandfather survived only because he had learned to swim. Before that, my great grandfather Bernard Fitzpatrick fought with an infantry regiment called the Connaught Rangers, serving between 1888 and 1918 in Malta, Cyprus, Egypt and the Second Boer War in South Africa. On today’s tour with Eric Deprez, my thoughts are drawn to the young men who were conscripted from around the villages where I was born and grew up in Ireland, and who were slaughtered in their thousands at Messines Ridge closeby and in July 1917 at Passchendaele. Their bodies lie here in Belgium, not far from the location of Kasteel Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck.

I try to reflect on the Passchendaele beer. I’ve visited the brewery and talked to Van Honsebrouck staff. I’ve seen the story behind the brand, and the reality behind that story. But I’m still confused about whether it’s a cynical marketing ploy to capitalise on the high profile of the war’s centenary commemorations, or whether it’s a noble act of remembrance.

On one hand, the Van Honsebrouck team are shrewd commercial operators, with staff who have previously worked at breweries such as Anheuser Busch Inbev where branding often comes before brewing and where margins are usually king. Part of the proceeds from the beer were donated to Stad Zonnebeke between 2014 and 2018 to help fund commemorative events, noble and appropriate, but today all profits from sales of Passchendaele beers are retained by Van Honsebrouck. And even if Brouwerij Van Honsebrouck are the brewery more geographically entitled to brew a beer called Passchendaele than any other, is the self-righteous language which is used on the bottle label—“with every sip, we reflect on the horror of the Great War”—really necessary?

On the other hand, this happened. It happened here. It happened no matter how much we would like that not to be the case. For people like Eric Deprez and Xavier Van Honsebrouck and for Frederic Boulez and Marc Schrauwens and for Johan “The Mole” Vandewalle and all the people who live here, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of gravestones, in almost every village, it’s part of the story of where they’re from. Perhaps on a deeper psychological level, living with so many corpses and so much terror underneath your feet, it’s appropriate to acknowledge the tragedy with a bespoke beer, to ensure it is remembered and perhaps to process a shared human grief. I encountered no ignorance or flippancy from those at Van Honsebrouck about how those who fought here suffered. Are the Passchendaele beers simply a fitting nod to the cultural history of this place?

As we make our way back to our cars, I ask Eric one more time about the branding of Passendaele, and whether he understands why people may be uneasy about it. He explains that the reason he has taken me to Café Taverne de Dreve to meet The Mole is to remind me that there are unknown stories that need to be remembered. We should be drinking to the Zonnebeke Five, not forgetting about them.

And then he tells me about a time recently when he stood for the Last Post at the Menin Gate and greeted a Belgian politician, who he doesn’t name. The politician told Eric that he didn’t think it was a good idea to sell beers named after the Battle of Passchendaele.

Eric Deprez re-enacts his response to the politician for me, more animated and passionate now than he has been all day: “All the years that I’m standing at the Menin Gate, I never saw you. A hundred years [since the] First World War, you’re standing here and staying in a hotel paid for by the State. And you don’t even know what it means, everything you see. So put your feet on the ground and ask before you say things which you don’t even have a clue about it.”

And with that, we drive onwards, to visit another cemetery, and afterwards, to grab another beer.

*